10-year old Ekukanju* and his six younger siblings have been out of school for the past ten months. Their father, a journalist, was forced to go into hiding for his anti-corruption reporting and can no longer work to pay for their schooling and care. ‘We are staying with our mother and uncle here in Douala’, Ekukanju says sadly. ‘But uncle has a large family of his own so even feeding is difficult. I am thin like this because of under-feeding.’ Community members who have started to help the family don’t blame Ekukanju’s father for the hardship, however; they know he had good reasons to go underground.

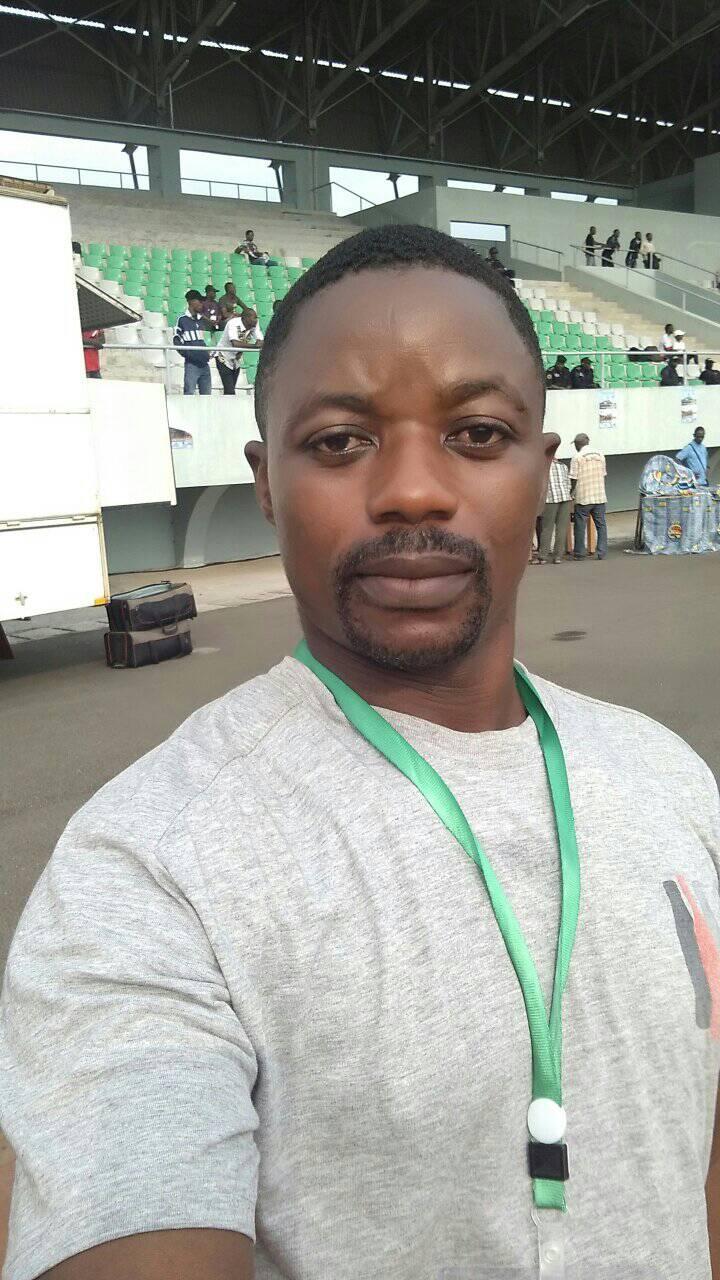

Telling the truth about the Biya regime is a very dangerous activity in Cameroon. Only two months before this conversation took place, on March 9th 2022, web editor and corruption whistleblower Paul Chouta was abducted from a Yaoundé bar where he had been watching football. He was brutally assaulted and left for dead. ‘I had gone outside during half-time when three unidentified men in civilian clothes in a green pick-up truck accosted me and threw me in their vehicle’, he said in an interview. ‘I shouted for help, but the attackers managed to push me inside and used my shirt to blindfold me’.

‘They told me that I’m stubborn and that I never learn a lesson.’

Chouta was driven to what he would later recognise as an area on the outskirts of the city, near the airport. There he was taken out of the truck and told to kneel. He recalls being beaten with stones, bricks, a baton and a whip, before finally falling unconscious. ‘They told me that I’m stubborn and that I never learn a lesson,’ Chouta says. It is not his first time being detained- he has been arrested in the past and assaulted by unidentified forces, as well as receiving several warnings to ‘stop writing rubbish’. ‘They said this time they will kill me, as I wanted to show that I was a hero.’ After waking up injured, naked and alone, Chouta walked in great pain for about two miles, before being found and helped by strangers.

A mayor and a timber company

A few months later Jean Francois Channon, the publisher of Le Messager, Cameroon’s leading privately-owned French-language daily, found himself under fire while being driven home from work. His driver managed to ‘skilfully manoeuvre’ and escape two individuals who shot at the car they were in. Channon says he believes that the attack was connected to his paper's coverage of a case of embezzlement involving the former mayor of a Yaoundé district’s dealings with a timber company.

Yet another reporter, who asked to remain anonymous, says he almost lost an eye in November 2021 while working on an investigation into a powerful and well-connected individual. ‘Men came to my house, broke in and assaulted me. I knew who they were but they said they would return to finish me off if I dared to mention their names. I had to move my kids across the border to a neighbouring country after that’, he said.

Evidence of torture

These journalists all survived, but some have not been so lucky. Chillen Music Television reporter Samuel Ajiekah Abuwe, nicknamed Wazizi, regularly talked about state corruption and human rights violations. He died on 17 August 2019 at a military hospital in Yaounde after going missing ten days prior. According to his lawyer, Christopher Ndong, Wazizi’s body bore evidence of torture. He had been denied bail under the Anti-Terrorism Law of 2014, which allows for indefinite detention without charge for offences including ‘acclaiming terrorism in the media’. Terrorism is defined by the law as anything that ‘creates a crisis situation’ or ‘insurrection’ and has widely been used by the security forces as an excuse to detain peaceful protesters and activists. Data collected by the ZAM team shows a steady increase in state human rights violations of citizens in recent years, mostly carried out under the auspices of this law. That data can be accessed here.

The charges included ‘hostility against the fatherland’

Among the hundreds of documented cases, at least eighteen journalists have been detained or forced into exile after the law’s passing in 2014. They include Radio France Internationale’s Ahmed Abba, who reported on refugees and conflict areas in the country and was arrested in 2015, and documentary producer Achomba Hans Achomba, whose turn came in 2017 when he was targeted for filming anti-government protests in southwest Cameroon. The charges against them included ‘complicity in hostility against the fatherland, secession, propagation of false news, insurrection, incitement to civil war, and complicity in acts of terrorism’, and both were tortured. Achomba was eventually freed after months of international pressure, while Abba spent two years in detention. They both now live in exile in Nigeria.

Armed struggle

Ironically the regime’s longstanding repression of any and all peaceful protests, including restricting their coverage in media, is what led to the insurgent situation in the South- and NorthWestern areas in the first place. In 2016 this largely-Anglophone region was gripped by popular protests denouncing the reigning Yaoundé-based Francophone elite’s perceived discrimination against English speakers. However, it was the central regime’s harsh military response which caused it to turn into a fully-fledged armed struggle a year later.

The crackdown on both protest and journalism has meant that Cameroonian media has less and less room to manoeuvre as it attempts to cover security forces’ human rights violations. The fear is especially tangible in Anglophone areas, where state operatives can order any individual to hand over their mobile phone and use whatever they find on the device to underpin a terrorism charge. This practice is also gaining ground in Francophone areas, too, with reporters being arrested in the context of general anti-government protests.

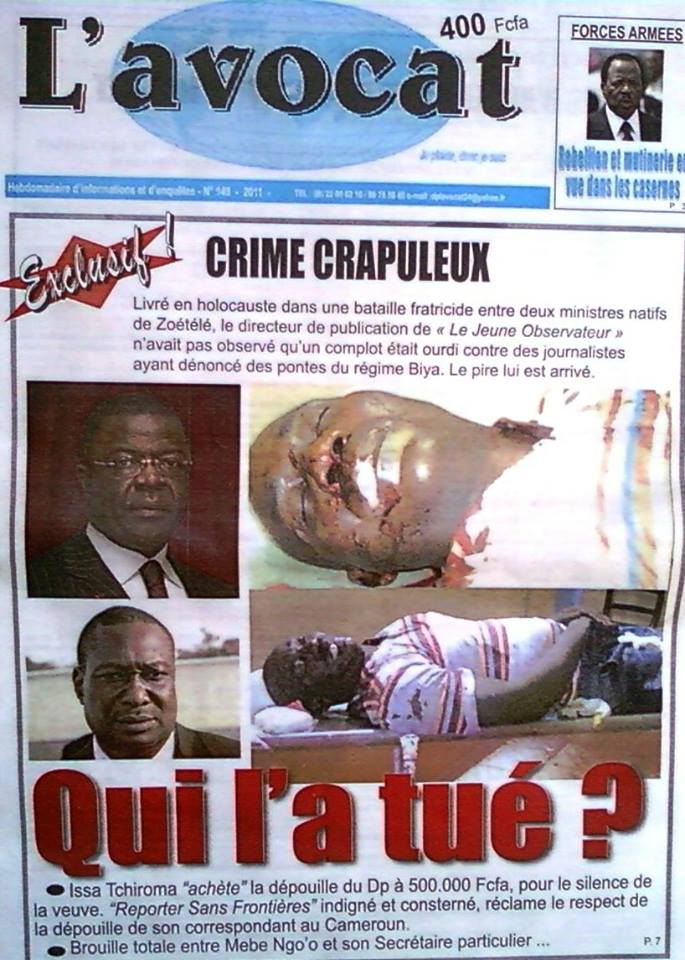

Regime-friendly publications defend their sponsors

The main victim of this repression is the truth, but in Cameroon, there is an extra twist. With truthful reporting made all but impossible, many in the ruling elite have seized the opportunity and launched publications to pump out false news praising their proprietors and smearing opponents. Despite shrinking press freedom the number of registered broadcasters and publishers has doubled in just the past three years, from three hundred to six hundred. L’Anecdote and Vision4 TV are both owned by Amougou Belinga, a prominent tycoon whose proximity to power may be related to the state’s decisions to accord him favours including a large bank loan without collateral and a US$4 million treasury grant. Other regime-friendly publications, including Quotidien Réalités Plus, Essingan, Le Quotidien and La Grande Tribune, share L’Anecdote's habit of remaining dormant until a sponsor is accused of theft or corruption, then abruptly returning to the newsstands to smear accusers.

Smear campaigns and prison sentences

Nsom Kini, the Guardian Post’s Yaounde bureau chief, notes that ‘those newspapers come out like dogs, to attack the adversaries of their masters, especially during elections’. Denis Nkwebo, President of the National Syndicate of Cameroonian Journalists says he feels ‘disgusted and disheartened’ by watching ‘media houses and newspapers fight each other over stories concerning embezzlers and thieves,’ adding that ‘instead of tackling the thieves, the media outlets owned by the thieves are vigorously fighting against any media house or newspaper exposing their sponsors.’ He blamed the fake news attacks and smear campaigns for contributing to a general climate of fear. ‘Even those who in the past were outspoken about thievery in public institutions are today silent, very silent indeed. Some who started excellent investigations ended the stories halfway and never cared to tell their readers why.’

Those who still try to keep the Cameroonian public informed about state mismanagement and corruption scandals find the machinery of the state directed against them even if they are civil servants. State-owned broadcaster CRTV’s general manager Amadou Vamoulke (72) was sentenced to twelve years imprisonment for embezzlement on 20 December 2022, despite the prosecution’s charges and evidence being widely dismissed as fabricated and a ‘sham’**. Prior to his arrest six years ago, Vamoulke himself had blown the whistle on the theft of public funds within the corporation. He had also attempted to reform and professionalise the organisation’s hiring policies. At present 80% of the station’s senior positions are reported to be occupied by members of President Biya’s immediate clan, leaving taxpayers to wonder whether the best people are being hired for the job. Even in Cameroon’s crowded media environment, however, few papers remain free to ask such questions.

The fraud investigator was transferred to the war zone

Silence also surrounds the case of Health Ministry official Dr Albert Ze, who was transferred to Bamenda, in western Cameroon, after he worked on several audits that uncovered the theft of health project budgets by powerful individuals in the state. In a rare interview, Ze told ZAM that his recent transfer follows years of harassment, including death threats as well as offers of bribes. ‘When I refused to take money, I was physically attacked. My house was burgled twice, with laptops, hard disks, and tablets stolen both times. Several batons were also left behind in my house as a message that they could be used against me.’

But after Ze’s attention was caught by irregularities around a COVID-19 Solidarity Fund that had amassed donations from corporate bodies and individuals in Cameroon between 2020 and 2021, things took a sudden turn for the worse. After word got out that he was ‘sticking his nose into business that did not concern him’, as ZAM’s sources put it, he was informed that he was to be transferred to the Regional Delegation of Public Health in Bamenda. As a Francophone and a member of President Biya’s Beti clan, this posting to the heart of an Anglophone anti-Biya region, where rebels are known to attack those perceived to have ties to the governing elite, this transfer posed a considerable risk to his physical safety. While reluctant to comment in detail, in a recent interview he says that ‘this situation has brought about a regression in my activities’, adding that he has had to ‘separate from his family, leaving them in a safer area’ and that he now lives alone.

Albert Ze’s colleague, Dr Nancy Saiboh, who had been set to participate in the same audit, also received a similarly abrupt transfer notice sending her to a rural area. Dr Saiboh told ZAM that she has since received threats by ‘unknowns on Facebook’ and that she ‘always looks over her shoulder wherever she goes’ nowadays. ZAM’s investigations suggested that eight other whistleblowers of state mismanagement and corruption were also targeted for harassment, threats, arrest and sometimes torture. However, when the investigations team made efforts to interview those eight individuals, none agreed to talk to us. Instead several expressed anger at being identified.

‘The IMF is complicit’.

Besides journalists and whistleblowers, hundreds of ordinary citizens have also been arrested, detained, tortured and jailed under anti-terrorism laws. These include members of the anti-corruption NGO Stand Up 4 Cameroon, whose president Kah Walla also serves as president of the opposition Cameroon Peoples Party (CPP). When asked about the attrition rate she doesn’t mince her words about those responsible. ‘They feel we are trying to remove the gombo (okra stew) from their mouths’, she says.

Walla, who has been detained herself, is known as the ‘Iron Lady’ in Cameroon’s progressive circles. She says she is disappointed at the lack of support from the international community. ‘We at Stand Up 4 Cameroon called on the International Monetary Fund to demand accountability for a loan of US$335 million given to Cameroon for the fight against COVID-19. The IMF did not; instead, they gave more money to the Cameroon government. This is complicity.’

The IMF’s US$335 million has been the object of an investigation by the Audit Bench of the Cameroon Supreme Court, which reported that it had recommended ten individuals for prosecution for embezzlement. However, the names of the ten have not been made public and the report has not been presented to parliament.

‘The tigers are fighting back’

Even officials at CONAC, the anti-corruption commission, would not talk to us on the record. Like their colleagues at ANIF, the Agence Nationale d’Investigation Financière, they recognise that the office exists mainly because of donor pressure rather than any political will. ‘These ‘tigers’, (a common nickname in Cameroon for corrupt politicians), ‘are fighting back ferociously against us and all those exposing them’, said a CONAC official, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

CONAC’s most recent report, which covers 2020, estimates that in that single year the ‘tigers’, which include ministers, directors of state corporations and government subsidiaries, highly-placed government officials, and senior military and police functionaries, together presided over the theft of approximately US$2 billion of state funds, equivalent to 20% of the country’s 2022 budget. Their reports fall on deaf ears, however; in 2018 alone CONAC transferred 94 dossiers of embezzlement and theft to various courts in the country for prosecution, but to date, none have reached trial.

*Name changed

**Despite calls for Vamoulke’s release being made by several international organisations, including Reporters Without Borders, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Cameroon has not responded. In a statement after the verdict, Reporters without Borders slammed the case as a ‘monstrous frame up’.

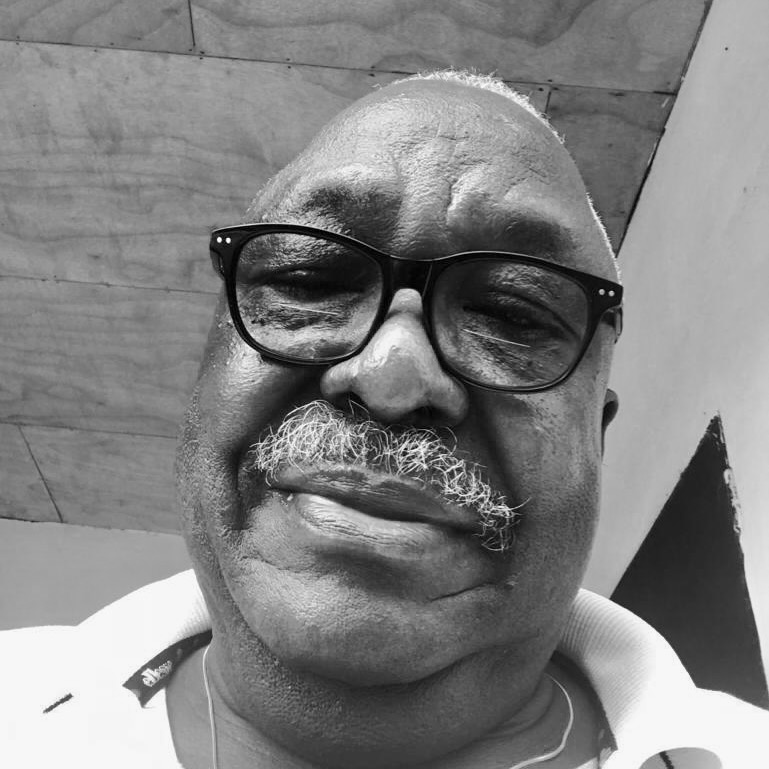

Chief Bisong Etahoben is a veteran Cameroonian investigative journalist and editor whose newspaper, The Weekly Post, was forced into bankruptcy in the early 2000s by state officials. He has often been threatened, and attacked in government media, and was physically assaulted during a recent investigation into a prominent Cameroonian billionaire. Acting as a mentor and local editor for Cameroon in this transnational project, he and his colleague Elizabeth BanyiTabi experienced how fear has gripped citizens throughout the country. ‘Several victims of the kleptocrats refused to talk because they feared for their lives’, he says.

Elizabeth BanyiTabi is an award-winning reporter for The Post Newspaper, Cameroon's most-read English daily. She has also worked online and on the radio. In 2021, she was part of a UK Guardian team that investigated the aftermath of the drowning in Turkey of a Cameroonian-born migrant. Shortly after, she investigated the impact of armed conflict on displaced young girls who had turned to prostitution for survival. For this investigation, a collaboration with Chief Bisong Etahoben, she had to strike a balance between protecting terrified sources and unearthing the truth. ‘They say that freedom of speech is guaranteed but freedom after speech is not guaranteed’, she says. ‘But we managed to go beyond the fear.’ BanyiTabi holds degrees in Women’s Studies and Mass Communication.

Read all the investigative articles in this series:

Cry Freedom | Trends of repression and resistance in five African countries

Nigeria | Death by tax collector by Theophilus Abbah

Uganda | How to remove a dictator remotely by Emmanuel Mutaizibwa

Zimbabwe | No human rights for ‘bad apples’ by Brezh Malaba

Kenya | The hidden cost of free and fair by Ngina Kirori

Human rights violations 2017-2022 in Nigeria, Cameroon, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Kenya