'There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river and go upstream to see who is pushing them in.' (Ascribed to the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu)

Executive summary

Many young people are risking everything to leave home in search of greener pastures within and outside Africa. They are pulled by promises of jobs and wealth, but they are also pushed: by autocratic leaders who treat state coffers as piggy banks and political opponents as criminals. Aware, urbanised, educated and social media savvy, a booming new generation of young people are simply fed up with settling for so little. Meanwhile, their leaders remain in power thanks in part to the support, whether tacit or direct, of the same wealthy nations whose budgets for fences and border guards get higher every year.

But change begins at home, and change surely is beginning. Tumultuous elections, protests and social media waves are all rocking the foundations of old patronage structures. This presents a growing headache for even the most entrenched despots, forcing a continual update of their systems of oppression to ward off new forms of dissent. As detailed in this report, the nations we examined all witnessed an increase in forms of police brutality and targeted surveillance, as well as laws outlawing online criticism and ‘computer misuse’, broadening interpretations of the term ‘terrorism’ and even the use of money laundering laws to stifle critics. But there are reasons for optimism, too; from the positive stories of Kenyans protecting their votes to examples of citizens who, in the face of overwhelming odds, simply continue to resist.

Increasing surveillance

The nations that were part of this investigation all witnessed an increase in forms of social media surveillance in recent years, as well as laws outlawing online criticism and ‘computer misuse’, a broadening interpretation of the term ‘terrorism’ and even the use of money laundering laws to stifle undesirable activities. Meanwhile those who still take to the streets to protest have found themselves being met with worsening police violence; in all five countries, assault, detention and murder by security agents are on the rise. And in a shift, both states and individual players seem more willing than ever to use plainclothes security officers and mercenaries to prosecute violence on their behalf.

Activists in all five countries called on the international community to back up their stated ideals with action. People we spoke to in three of the five countries pointed out the bitter irony that the donors who have loudly spoken about human rights and good governance commitments are the same nations whose aid money, given for cynical geopolitical reasons, is instrumental in propping up abusive governments.

Despite the five countries differing substantially in terms of their histories, cultures, languages, socio-political structures and geography, a number of interesting parallels emerged:

1. Technological developments have upended the landscape of social struggle. On one hand, thanks to social media and smartphones, populations across the continent are increasingly able to witness the liberties and public services enjoyed by populations elsewhere, which in turn is driving citizens to demand more of their leaders. Social media also helps amplify and spread such demands. But it is these same surveillance technologies which are enabling oppressive leaders to target ‘troublemakers’ more effectively, leading to the kidnapping and detention of individuals (including journalists) who get blamed for these demands for change.

2. A younger, more demanding, educated and urbanised voter cohort is changing the ways in which leaders are held accountable, using access to information to evaluate what their leaders are doing (or not) and formulate precise demands for improvement.

3. Donors and the international community find themselves under the microscope, putting the West finds itself between a rock and a hard place while witnessing the revival of Cold War dilemmas. Do they continue with contracts and stable partnerships in Kenya and Uganda, or listen to civil society? Should they indulge Cameroon’s kleptocracy, or risk it sliding more towards Russia?

4. A spate of new and updated laws have appeared across the continent, all ostensibly above board but conveniently broadly worded. These include Nigeria’s regulation of cyberstalking, the Surveillance and Computer Misuse Act in Uganda and new interpretations of a recent anti-terrorism law in Cameroon, not to mention a Patriotic Bill in the making in Zimbabwe. Money-laundering laws have also been pressed into service as a tool for strangling the finances of opposition activists and parties in Cameroon, Kenya and Uganda. These shifts present a problem for progressive movements, but also indicate that governments appear to be aware of the need to maintain a veneer of democracy for fear of being dumped by donors.

5. While many African leaders have found foreign powers and internal opponents to be useful scapegoats for domestic problems, there does appear to be at least a rhetorical shift in progress, with leaders in Kenya, Uganda and Zimbabwe all changing tack and attempting to convince their citizens that things are better than they seem. In Nigeria, presidential candidate Peter Obi’s manifesto for the coming elections makes very specific commitments regarding assistance for farmers, clean accounts and a reliable electricity supply.

Country summaries

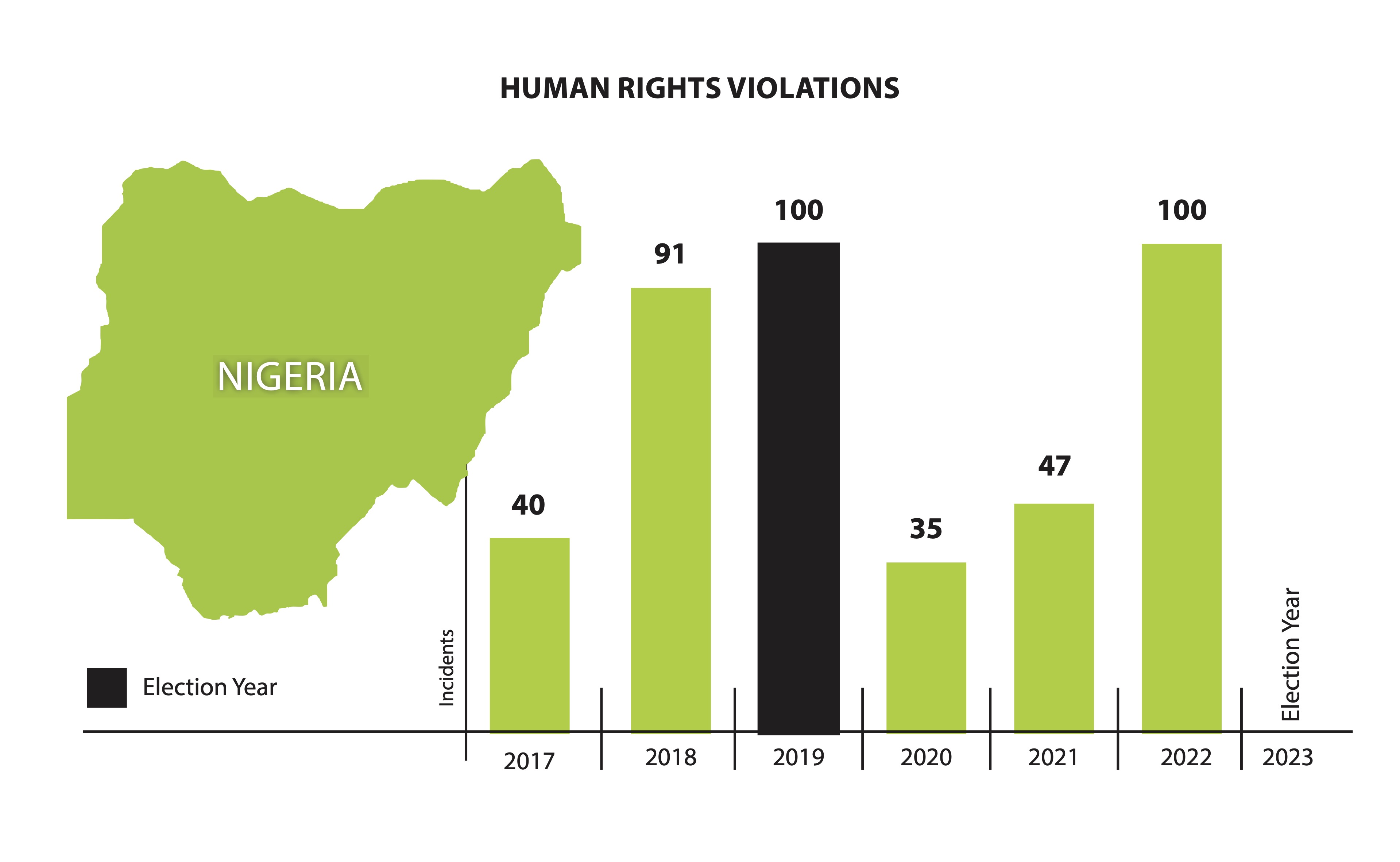

Africa’s most populous and second wealthiest state, Nigeria distributes its political power through a federal governance system comprising 36 states. These regional seats, with their large budgets and limited oversight, have proven as fertile ground for low-grade corruption as the federal government, and in turn, have become desirable properties to be fought over increasingly violently. Informal militias of young men, sometimes clad in T-shirts proclaiming support for regional leaders and their parties, are allowed to operate as so-called ‘tax collectors’ or ‘bodyguards’. In exchange, they support their patrons by attacking opponents, with victims including critics, journalists, opposition party supporters and political activists. The nation pays a price too, with large swathes of the country now dominated by terrorists, insurgents and bandits. Sabotage and kidnapping for ransom have become worryingly common, and the states seem incapable of dealing with the enemies in their midst, perhaps because a bandit might also be a ‘tax collector’ in a different t-shirt.

Various reports chronicling the country’s litany of human rights violations indicate that the Nigerian army is not immune either, and increasingly suffers from ill-discipline and warlordism. The federal government appears to be out of ideas as to how to overcome the rising anarchy, too, and seems to be adopting the same tactics as the regional leaders against those it deems enemies: target individuals, either with plainclothes operatives, thugs, or legitimate arrest if a charge can be found, or clamp down violently by deploying the army against mass movements, as happened with #EndSARS, a nationwide protest against a murderous and extortionist special ‘anti-robbery’ police squad.

The government’s failure to deal with flooding, security, farmer-herder clashes and hunger are at the centre of an upstart presidential campaign by a rank outsider: Peter Obi, who brings with him a tolerable record of good governance while serving as governor of Anambra State, where he made improvements in the fields of law and order, education, government salaries and roads. It is of course fanciful to imagine that one man can sort out the mess that is contemporary Nigeria, but his political supporters, known as the ‘Obidients’, are pinning their hopes on him to find solutions to banditry, anarchy, the effects of climate change, and rampant unemployment.

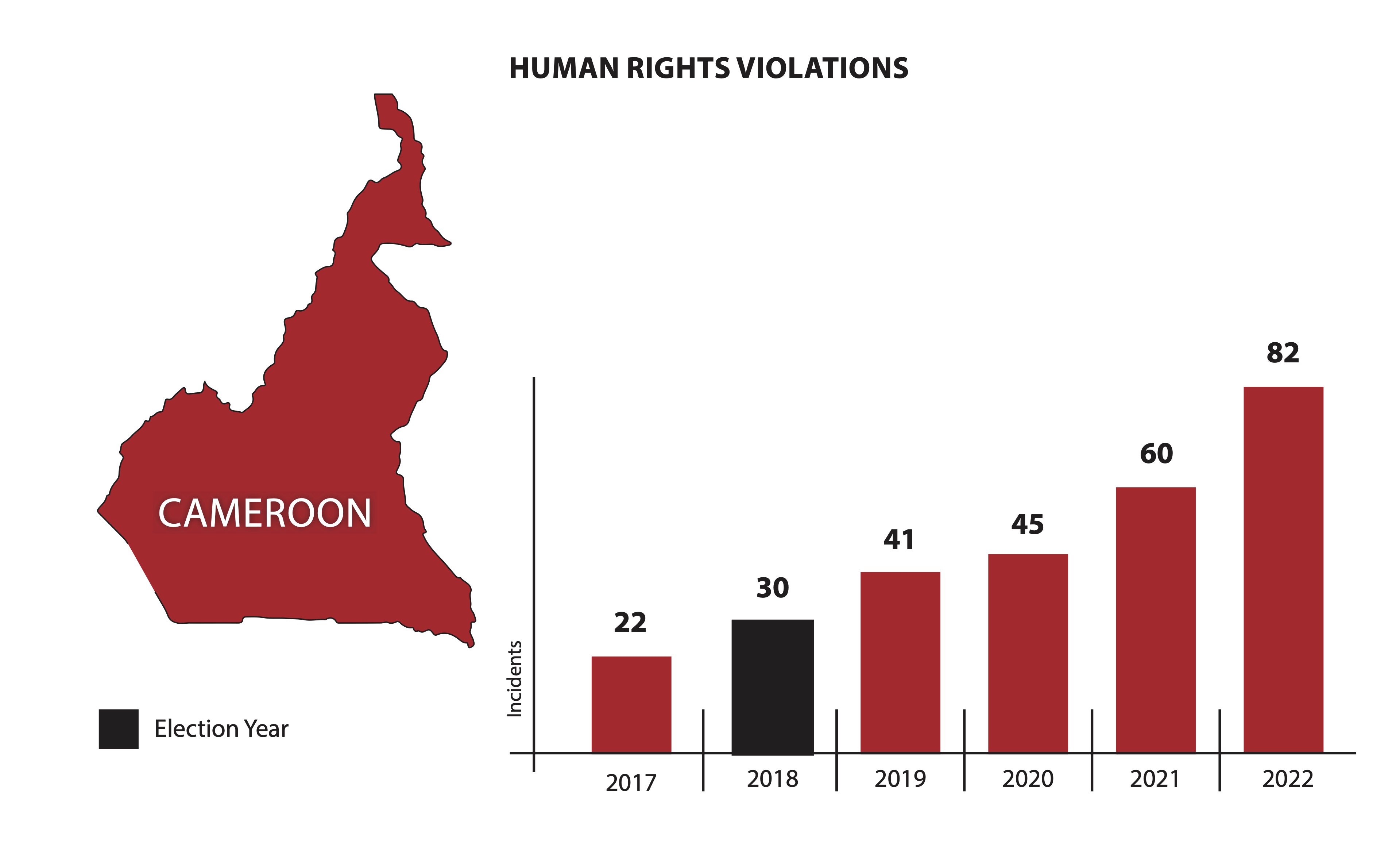

In Cameroon, the truth itself is in the crosshairs. 89-year-old kleptocrat Paul Biya’s embattled and dysfunctional regime, which is increasingly constituted almost entirely from his own Beti clan, can seemingly only justify itself by promoting an alternate reality. So as on one side it busies itself with persecuting journalists who expose the patronage system and its kingpins, it is also founding and subsidising its own media houses tasked with singing the regime’s praises and slandering its opponents. Critics risk lengthy jail terms, too; by stretching the definition of ‘terrorism’, the law can ensnare almost any critic or opponent. Hundreds have been arrested and detained, with at least one detainee dying as a result of torture. Unidentified plainclothes operatives have also kidnapped, assaulted and murdered critics of the regime.

Though united around a francophone identity, the regime is just as merciless to francophone critics and state functionaries who step out of line. Civil servants who have tried to scrutinise money flows (including in the case of COVID funds) or have appointed subordinates based on competence instead of nepotism have been met with dodgy transfers or jail. In the case of one francophone health worker, his transfer to anglophone territory- where an insurgency against the regime is raging and specifically targeting francophone state officials, has put him in harm's way, seemingly deliberately. Opposition parties, along with civil society organisation Standup4Cameroon, are publicly demanding a stop to new IMF loans to the country until the government accounts for earlier ones.

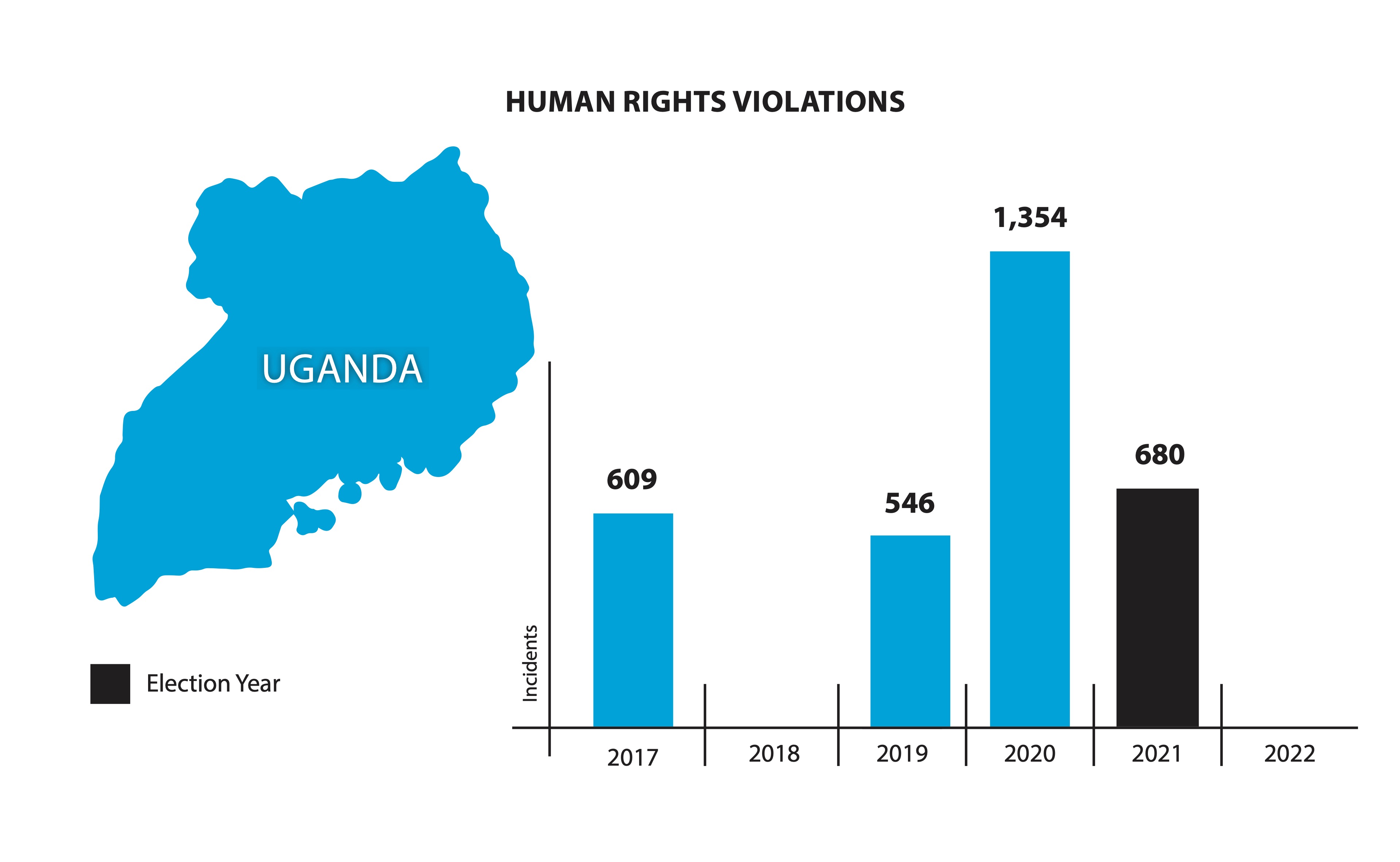

Ageing autocrat President Museveni’s de facto one-party state is approaching its 37th birthday and struggling to mount a compelling argument for its own continued existence. It’s a challenge because a significant majority of the population has known no other president and while they’re becoming increasingly disaffected and resentful, they’re also increasingly old enough to vote. Elections in 2021 were branded the least fair and most fraudulent ever, with mass kidnapping and detention of opponents as well as the brutal suppression of protests. But the population is young, educated, and vocal, and they’re very online, following and engaging with the rebellious accounts of intellectuals who criticise and mock the ageing dictator. A particular target of mockery is Museveni’s ‘secret plan’ to establish an imperial presidency by grooming his son, General Muhoozi, to take over power. Drawing energy from the social media criticism and ridicule, organised political opposition is also growing.

In response, the regime has deployed three types of repression: one, using the law as a weapon, particularly concentrating on the regulation of digital speech, including with the recent Computer Misuse Act; two, targeted violence, deploying unmarked vehicles that kidnap critics, critical journalists and opposition activists to face detention and torture; and three, financially strangling civil society organisations, including by cutting off a key basket fund that European donors used in part to sponsor pro-democracy players. The state’s decision to force the closure of this fund even though it’s also a vital source of state patronage indicates how seriously the threat posed by civil society is judged to be. In 2021, recognising that the state’s donor funding base was propping it up unnaturally, five of Uganda’s opposition leaders urged donors to suspend all but the most essential humanitarian aid to their country.

This seems like it may be hard to get donors to agree to, though. Museveni has succeeded in establishing Uganda as a key ally of the US and a pivotal regional presence in their fight against Islamic terrorism. In return, the United States supports Uganda with nearly US$1 billion a year, while another billion flows from other countries and institutions like the World Bank. Much of this funding is project-based, and very little ends up in state budgets, but anything paid for by donors is one less thing the state needs to find the money for. Meanwhile the Ugandan military, which is deeply embedded within the civilian state, has benefited enormously from its role as the American partner of choice in the region. The US has trained more troops from Uganda than from any other country in sub-Saharan Africa except Burundi.

The militarised ZANU-PF regime of Emmerson Mnangagwa clothes itself in civilian good governance and social justice rhetoric. Numerous speeches and pronouncements work hard to show that the government is really trying to provide health care and education, but that they are being hamstrung by Western sanctions. Justice minister Ziyambi Ziyambi has even gone so far as to blame human rights violations on sanctions, arguing that if there were no sanctions, there would not be any malcontents and thus no reason for clampdowns.

ZANU-PF misinformation about good healthcare efforts can verge on the ridiculous at times. After the government circulated photoshopped pictures of pristine hospital wards, journalists visited state health structures and documented the actual and very dilapidated health facilities. Pictures have also surfaced of Zimbabwean export goods for sale in European and American shops, proving that forex is most definitely reaching the country while the government pleads poverty. Political opponents and critics point to abundant evidence that Mugabe’s departure brought no change, and instead of a well-meaning government a kleptocratic and abusive military remains in power. They also underscore the vital foreign partnerships, particularly with Chinese companies in mining ventures, which serve to enrich the governing military-political elite rather than state coffers.

As it senses itself losing the information war, the ZANU-PF government is increasingly resorting to arresting and detaining critics on spurious charges such as ‘disturbing public order’. The COVID lockdowns became a convenient means to stop street protests, while massive violence put a halt to social media’s #ZimbabweLivesMatter campaign that had attracted a lot of support in 2020 and 2021. Courts, under pressure from above, now routinely treat dissenters worse than actual criminals and those accused of corruption, while several new laws clamp down on protest and civil society organisations. Civil society in turn has appealed to old constitutional guarantees and human rights laws, and has petitioned the UN, SADC and AU to help pressurise the government as it seeks room to campaign for the 2023 elections. Meanwhile the repression and deteriorating social conditions have combined to drive an exodus of citizens: an estimated third of the population now lives outside the country.

More Kenyans than ever voted for independent candidates or rejected calls to vote along ethnic lines. Many simply stayed home altogether, while candidates desperately tried to attract votes by making what was described as ‘wild promises’, of stipends and loans to help poor families, and of an end to corruption, without saying how. A sinister undertone to the campaigns underscored how seriously incumbents and aspirants approached the whole exercise: at least 73 attempts to influence counting at poll stations were registered, while one elections official was shot in the leg after refusing to alter the count and another one was murdered. Two individuals related to the recent ICC trial of now-President William Ruto turned up dead during the campaign period too. No matter who won at the polls, though, civil society still came off worse. To quieten an increasingly vocal civil society, the state proposed new regulations that make it harder for CSOs to receive financial support from abroad.

For their part, the same Western donors who partner with the government while also funding pro-democracy NGOs seem to have become more reluctant to work with the latter. According to author Ngina Kirori’s sources, this may be because important contracts and investments are at stake, and few countries are willing to cede such economically and geopolitically important ground to China.

Nevertheless, faced with a populace that is younger, more engaged, and more insistent on change than ever before, the previously monolithic political establishment is showing cracks.

Evelyn Groenink is ZAM’s investigations editor and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. Having co-founded the Forum for African Investigative Reporters in 2003 and the African Investigative Publishing Collective in 2015, she has led and edited over a dozen transnational investigations on the African continent. She has also produced a detailed five-part series for ZAM titled ‘Between Bitter Almonds and Good Hope’, on South Africa’s slide into corruption under the government of Jacob Zuma. Her latest project is ZAM’s ‘Anatomy of African Kleptocracies’ series of investigations, of which this transnational investigation project forms part. She has published seven books; five in the Netherlands and two in South Africa.

Read all the investigative articles in this series:

Nigeria | Death by tax collector by Theophilus Abbah

Cameroon | The truth is a dangerous business by Chief Bisong Etahoben and Elizabeth BanyiTabi

Uganda | How to remove a dictator remotely by Emmanuel Mutaizibwa

Zimbabwe | No human rights for ‘bad apples’ by Brezh Malaba

Kenya | The hidden cost of free and fair by Ngina Kirori

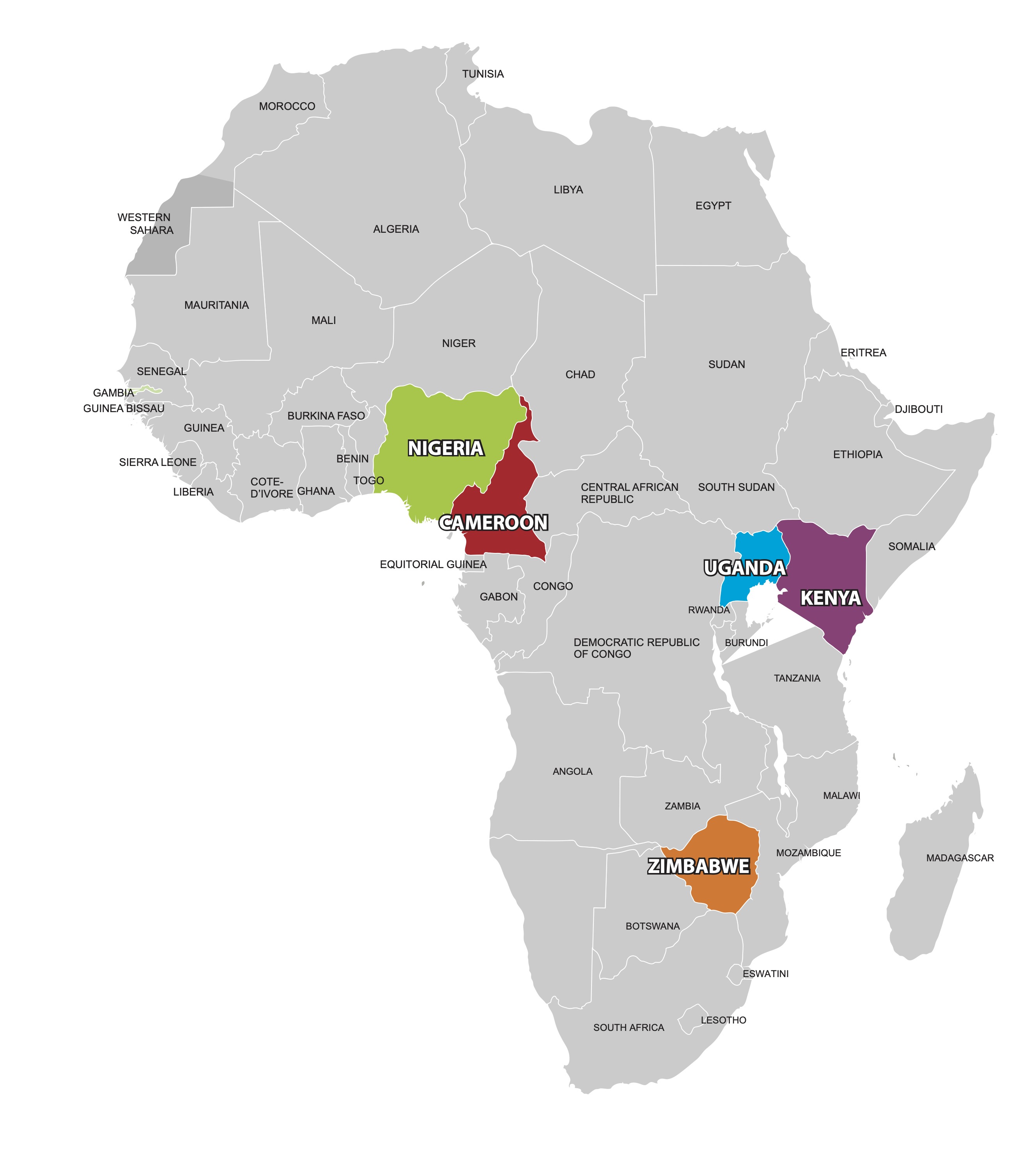

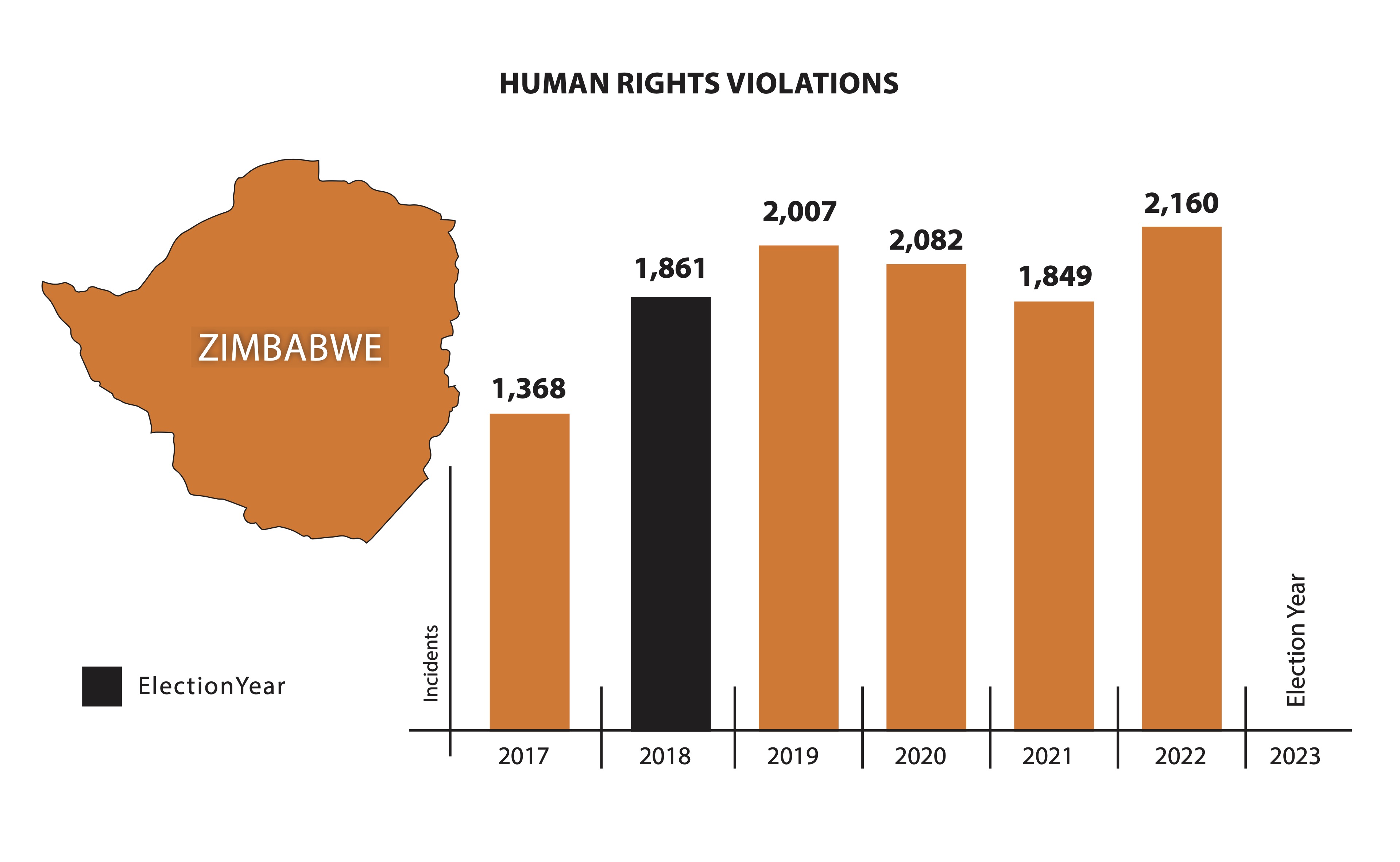

Human rights violations 2017-2022 in Nigeria, Cameroon, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Kenya