‘It is your man who is doing this’, shouts the woman, standing tall and pointing her finger. She’s speaking at a community meeting in Mawanga, Nakuru County, in central-western Kenya, and the man she is talking about is a local political candidate for one of Kenya’s main political parties. She’s referring to a recent spate of rapes and murders of women in the neighbourhood. In June 2022, three months before Kenyans went to the polls, five women were murdered in Mawanga in the span of two weeks. All suffered the same horrific fate; first raped, then killed and then their bodies set on fire. Those suspected of committing these crimes are known associates of the candidate in question. The woman whom she has been pointing at, a public supporter of the candidate in question, sits quietly in her chair.

The scene is from the documentary Ganglands, which was made by NTV’s Dennis Okari in the run-up to the Kenyan elections of August 2022. Besides revealing a broader trend of violence accompanying the scramble for lucrative political offices in Kenyan politics, it also reveals how sexual violence has, in the words of the Kenyan Human Rights Commission, emerged “as a weapon of subjugation.” ‘Those rapes are meant to send a message that a particular area has been ‘conquered’ by a particular group’, says the National Commission of Human Rights Defenders’ Executive Director Kamau Ngugi. In Ganglands, a former gang member explains that the purpose of the terror is to force the public to either vote for specific candidates or ‘not to leave their home altogether’.

Murder and rape

Both murder and rape have long been used to manipulate elections and intimidate the public in Kenya, targeting community activists and opponents of powerful candidates. A count after the previous elections in 2017 suggested that 92 murders and 201 rapes could be linked to the polls in that year. According to the Kenyan National Human Rights Commission, the Kenyan police force is accused of participating in these acts. A Human Rights Watch report said that there had even been “gang-rapes by men in uniform in opposition strongholds” in the run-up to the 2017 vote.

That allegation was strongly denied by police leadership as 'utter falsehoods’, but many other reports also implicated the police in incidents of extreme violence at the time, with multiple journalists reporting cases of physical assault by police officers, politicians or political operatives. The mysterious murder of Christopher Msando, ICT manager at the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) the parastatal tasked with overseeing elections in Kenya, also still haunts the memories of those elections. Msando’s strangled body was found in a forest a few days before the voting, with one of his arms showing deep cuts. Before his death, he had often joked about having a chip in his arm which granted him access to the election’s digital systems.

Choosing ‘a caring and committed representative’ was risky

According to most observers, the 2022 elections have been more free and peaceful. Speaking in an interview, Ramadhan Rajab of Missing Voices Kenya, an NGO that traces extrajudicial killings by the security forces, attributed this development to ‘various peace initiatives by civil society’ in communities. But some stories from voters, community activists and elections officials also indicate a growing trend among stakeholders and the public to ensure that democracy works. The recent vote’s lower incidence of violence is in part attributed to citizens who kept their heads, exercised their duties, and remained peaceful even in the face of perceived fraudulent and repressive activities.

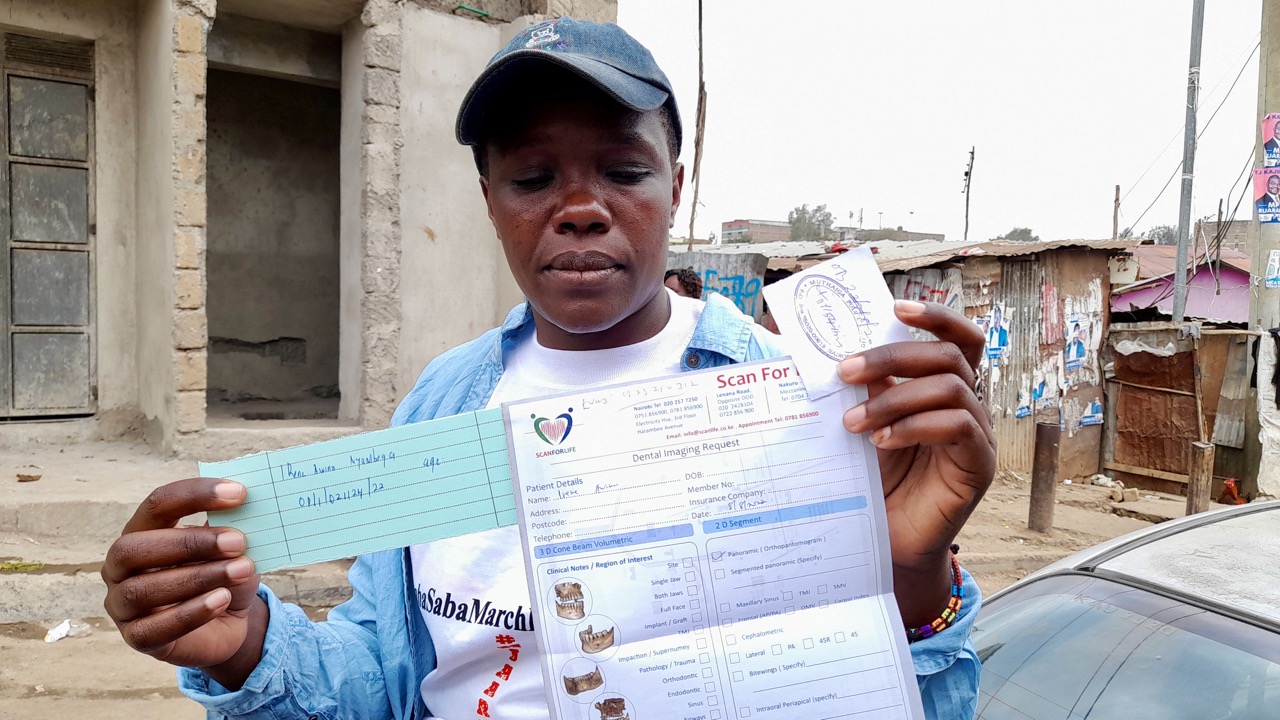

Nairobi resident and community leader Irene Nyambega, for example, stood firm despite being threatened and assaulted by a local neighbourhood watch group in her Mathare neighbourhood for displaying a poster of her preferred candidate in her window. ‘The group leader, whom I know as Abiola, asked me several times why I was supporting somebody “who does not come from the same tribe” and I said it is my right.’ Eschewing tribalism, Nyambega had chosen to support the candidate she felt would make ‘a caring and committed representative’. She refused to take the poster down.

A few nights later, she heard shouting outside her home, with a voice loudly stating that those supporting candidates ‘outside’ of the community’s dominant tribe needed to be ‘cleansed out of the neighbourhood’. ‘When I came outside I found Abiola and his group. He said that tonight he would be beating somebody up. Before I could ask him what he meant, he slapped me while the other group of men held my arms so I wouldn’t fight back. My daughter was standing near me, crying.’ Fortunately, a group of female neighbours came to her rescue, and the men left. On the night before polling day, Nyambega could not sleep out of fear. ‘People were hitting objects outside my door and sounding horns’, she recalls. But the same group of women who had earlier come to her aid again came to help, and together they made a plan. ‘Instead of waking up early, as would have been routine, we gathered the strength later and then went as a group to the polling station, then dashed back home.’

A request to alter forms

Similar bravery was displayed by Wajir County’s local IEBC presiding officer, Mohammed Kanyare, who was tasked with overseeing ballots in a remote area of north-eastern Kenya. Writing in an official report to the IEBC, Kanyare describes how on August 10th 2022, while headed to the tallying centre on foot to submit the results from his polling station, he was stopped by somebody in a car. The driver, Kanyare wrote, asked him to get into the car with him. When the elections officer refused, the man then asked him to ‘just alter’ one of the forms he was carrying. Kanyare again refused and continued to walk.

He reached the tallying centre safely and was preparing to submit his results to the national returning officer when suddenly the lights went out. In a moment of chaos, he recalls glimpsing a person who ‘looked like a policeman’, who approached and shot him in the leg. The wound was so severe that Kanyare’s leg later had to be amputated, but his courage protected the integrity of the elections in Wajir County.

In Embakasi East, on the outskirts of Nairobi, a similar event would claim the life of elections officer Daniel Musyoka. On the eve of the final tally, on August 10th 2022, colleagues described Musyoka abruptly looking ‘disturbed’ before locking himself in one of the rooms in the polling station office. He would not emerge until 4 AM, when he went home. After returning to the office at 9 AM, the elections officer went out to receive a phone call. CCTV footage shows him speaking to a motorbike operator nearby at around 9.50 AM. This was the last time he was seen alive. Herders found his body in a gulley while grazing their cows more than 50km away in Kajiado county, near the Kenya-Tanzania border. The post-mortem examination revealed the cause of death as strangulation.

The elections authority denounced the ‘forceful recruitment of voters’

In the words of the IEBC chief who spoke at his funeral, Musyoka was known to be a ‘competent professional’ who was ‘committed to free and fair elections’. Whether he had been asked, like Kanyare, to alter election forms, and whether that was the reason for his ‘disturbed’ behaviour the night before, remains a mystery. But at a later press conference, the IEBC itself cited his death and Kanyare’s injury as examples of the 33 attempts it counted by politicians and their operatives to ‘either bribe, intimidate or threaten elections officials’ in the elections of 2022.

The total tally of attempts by individuals exerting ‘undue influence’ such as bribery or ‘forceful recruitment of voters’ during the same polls as recorded by the commission was 73. Among these was one case of ‘unwarranted arrest’ of a voter education coordinator (held in a room at the national tallying centre by officers of an anti-terrorist police unit for three days), and several (unsuccessful) attempts to break into offices where computers with sensitive data were housed. on August 15th, during the unveiling of the general election results, the IEBC’s own leadership had also been attacked by political operatives who stormed the stage punching officials and even hitting some with chairs.

The very anger of these political figures might also indicate that something is changing in Kenya. In several areas where dominant candidates engaged in campaigns of intimidation, voters ended up electing their opponents regardless. This was the case in both Wajir County and Embakasi East. Even in Nakuru County, the area in which five women were murdered in a campaign of intimidation, a relatively unknown opposition candidate stunned the main candidates by seizing on public outrage to win by a large margin.

An independent mindset

Another sign that democracy may be ascendant in Kenya is the sheer number of independent candidates that voters have to choose from. 6000 independents stood throughout Kenya at the 2022 elections, an increase of 50% from 2017. Of these, 102 were elected to the 290-strong County Assembly, which represents Kenya’s 47 counties, a new record according to the registrar of political parties. Thirteen independents were also elected to Kenya's national assembly out of a total of 349 seats, as well as one gaining a seat in the 47-strong Senate.

Overall it’s a small but significant shift in Kenya’s political landscape, where dynasties and regional strongmen have dominated the political establishment in Kenya for decades, taking turns to govern in a patronage system that rewards friendship and loyalty instead of spending on services like health care and education. ‘I want to be different from those politicians who deem (being in politics) as a lucrative venture’, says Ndung’u Ithuku, who stood as an independent in Kabete, also just outside Nairobi. ‘In my campaign, we went door to door instead of spending money on branded vehicles, hype and other political goodies,’ Ithuku did not win this time but is, he says, ready to contest again in 2027.

The President proposed to disband the feared police unit

It even seemed a message of change had reached newly elected President William Ruto. After promising in his acceptance speech that his administration would look into cases where citizens had faced ‘intimidation, threats and in some cases murder’ during the electoral cycle, he proposed to disband the feared Special Service Unit (SSU). The SSU is an elite paramilitary unit believed to be responsible for hundreds of extrajudicial killings in the country, whose victims are often posthumously labelled as criminals or terrorists. On several occasions, sacks containing dead bodies with their hands bound behind their backs have been found in rivers in Kenya, and in his announcement, Ruto tacitly admitted that this was at least in part the work of the SSU. Police chief Amin Mohamed himself later confirmed the unit’s disbanding, saying that the decision would mean ‘no more extrajudicial killings in the country.’

Real change for the better remains slow, however. Like in the other countries in this investigation, the Kenyan state has purchased surveillance spyware that allows it to read messages and emails, and listen in on phone calls. Speaking in 2021, civil society activist Suhayl Omar said that ‘the Kenyan government relies heavily on surveillance of its citizens to crack down on any form of opposition”. By July 2022 that complaint still did not yet seem outdated when, a month before elections, activists and other social media users expressed concern about a Communications Authority decree to reregister SIM cards or face fines or imprisonment.’

None of the countries currently competing for contracts with the Kenyan government seem to be particularly concerned about new President William Ruto, however. This is despite his role in the post-election violence fifteen years ago in which over a thousand Kenyans died. Ruto's actions and tribalist rhetoric during the period led to him being charged with crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court (ICC), and though the charges against him were dropped in 2016, the court refused to acquit him, saying that a new prosecution could be opened in the future should fresh evidence be submitted.

This threat hanging over the new president’s head was recently connected to two more mysterious deaths. On October 26th prominent Kenyan lawyer Paul Gicheru, who was facing his own ICC charges after being accused of witness tampering on behalf of William Ruto, was found dead in his Nairobi bedroom with foam coming out of his mouth. Gicheru had been about to testify in that witness tampering case. Three months earlier Christopher Koech, a witness in Gicheru’s case, collapsed while on his motorbike in Kakamega county. He was also reportedly found to have foam coming out of his mouth. They are added to a bleak tally of eleven other witnesses connected to Kenya’s new president who have died since charges were announced against him in 2011.

Changed priorities

Meanwhile, President Ruto recently ordered another notorious unit, the General Service Unit, into Nairobi to counter a surge in violent crime. Missing Voices has documented another 23 murders and seven disappearances since August. Prosecution of offences committed by security forces also remains extremely rare and Kenya’s courts have reported a backlog of 60,000 of such cases. The murder of Christopher Msando in 2017 still has not reached a courtroom, despite a key witness declaring themselves ready to testify. A much-needed Witness Protection Agency, nominally in the making for years now, remains crippled by a lack of funds.

The lack of real institutional progress has civil society in Kenya clamouring for more support from Western donors for its pro-democracy and anti-corruption efforts, though there’s little success. ‘Priorities seem to have changed’, says the leader of one civil society organisation, who asked to remain anonymous. ‘Several reports we compiled on misuse of public funds have been met with silence, very little action and reduced funding.’ Asked why he thinks this is so, he replied that Western partner countries ‘are more concerned about doing business with the Kenyan government’ nowadays, especially ‘with regard to contracts that might otherwise go to China and the East’. Civil society sources also claim to be affected by Kenya’s 2014 rating upgrade which saw the country’s ranking upgraded to “Lower-Middle Income”. This makes it ineligible for various forms of support, including grassroots support, which is reserved for countries ranked as low-income.

Ngina Kirori is an investigative news reporter and broadcast editor for Nation Media TV (NTV) in Kenya with a track record of perilous undercover work. She is a respected voice in the coverage of social protests, facing teargas and arrests together with citizens and other journalists.

Read all the investigative articles in this series:

Cry Freedom | Trends of repression and resistance in five African countries

Nigeria | Death by tax collector by Theophilus Abbah

Cameroon | The truth is a dangerous business by Chief Bisong Etahoben and Elizabeth BanyiTabi

Uganda | How to remove a dictator remotely by Emmanuel Mutaizibwa

Zimbabwe | No human rights for ‘bad apples’ by Brezh Malaba

Human rights violations 2017-2022 in Nigeria, Cameroon, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Kenya