The protest movement should not betray women

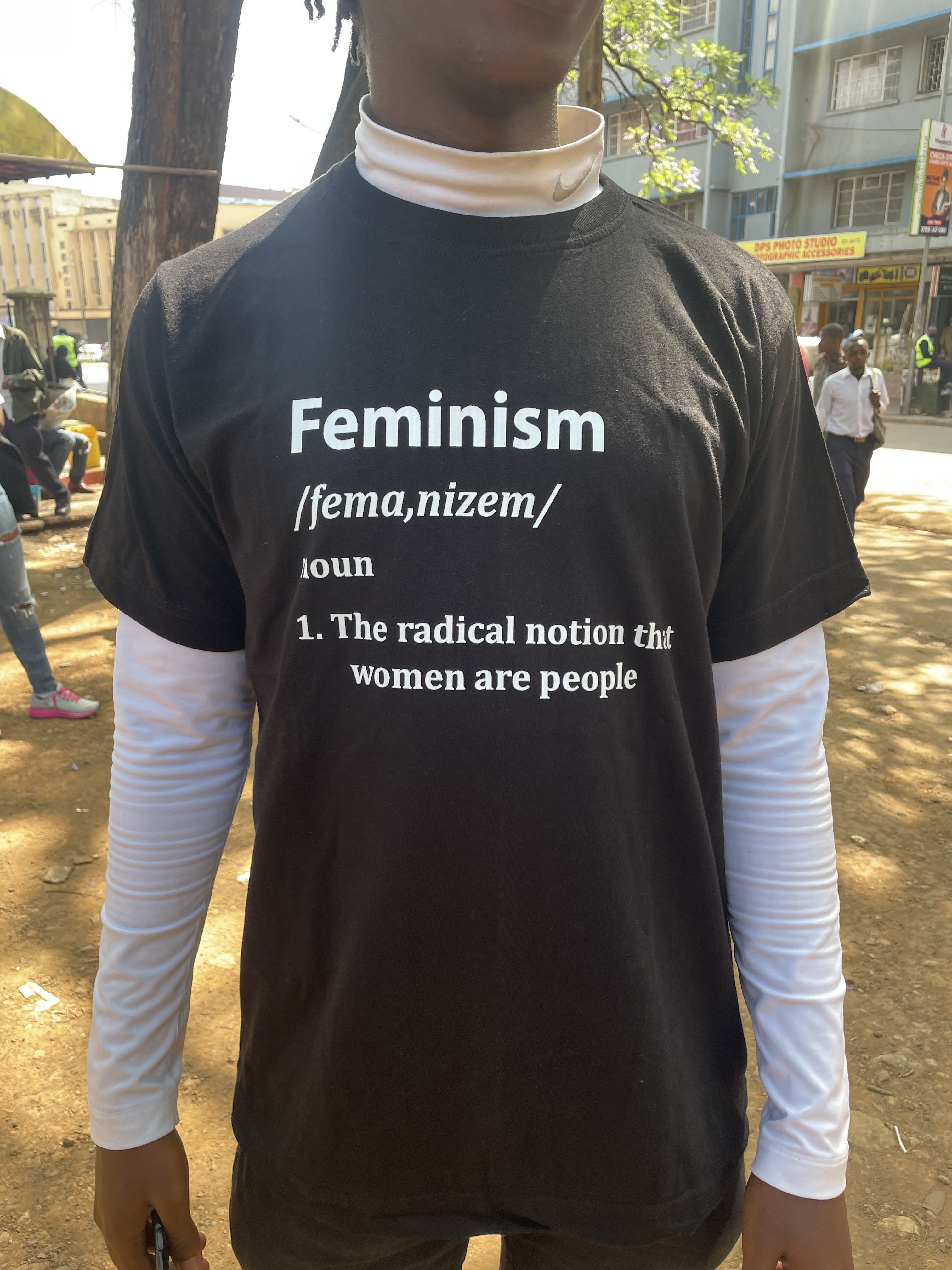

On 10 December 2024, I joined thousands of feminists in a nationwide anti-femicide march in Kenya. More than 100 recent reports of women being murdered—most at the hands of their intimate partners—prompted us to spotlight the connections between gender-based violence, poor governance, and the economic crisis, including the rising cost of living. This marked the second march against gender-based violence in Kenya in 2024, following the first in February.

During the march, a bystander—a fellow woman—asked me, “What are you people protesting about?” She seemed surprised that such a cause could galvanise us into action. After I explained our cause, her puzzled expression made it clear that the question was not malicious but borne of genuine ignorance—a sobering indictment of how normalised violence against women is in our society. It underscored exactly why we had to disrupt “business as usual” by bringing Nairobi’s central business district to a standstill.

Considering the Kenyan police force’s consistent track record of violence against protesters during the recent #RejectFinanceBill protests (1)—including unlawful arrests, killings, and abductions—we were fully aware of the risks involved in this march. Yet nothing could have mentally prepared me for what followed.

The police immediately responded with hostility

The police responded with immediate hostility, tear-gassing the first group of women as they arrived at our meeting point—before the march had even begun. Their tactics were clear: to break the crowd into smaller, more vulnerable groups and extinguish our momentum before we could march. The irony was bitter—the very agents of the state who assaulted us were the ones entrusted with protecting women from gender-based violence.

Yet, the police’s brutality only strengthened our resolve. Every assault forced us to regroup and return to the streets with renewed determination. A group of thirty of us then managed to march forward, facing off against the police with nothing but our placards and voices. Our message was loud and clear: stop killing women.

But as we approached the police convoy, they began firing rubber bullets and launching tear gas in our direction, the canisters exploding around us like fireworks. Amid the panic, I was injured—rammed into a parked motorcycle by another protester trying to escape. My ribs were bruised, and pain seared through my arm, but the police continued their assault, lobbing tear gas canisters into alleyways to scatter us like vermin trapped in a maze.

Eventually, I found my brother and a friend, and together we joined a group of fellow protesters seeking shelter in a nearby stall. We barricaded the gate and huddled inside, hoping to wait out the chaos. But as tear gas seeped through an open back door, we realised—too late—that the police had forced us into a gas chamber. Our throats, nostrils, and lungs burned unbearably. With no choice but to face the turmoil outside, we burst from the stall, eyes streaming and chests heaving.

2024 was the worst year on record

According to data journalism entity Odipodev, in collaboration with our media partners at Africa Uncensored, 2024 was the worst year on record for femicide reports. “We had (earlier) looked at 500 cases of femicide that had happened between 2016 and 2024, and a lot of action took place. There were protests and petitions taken to various counties, and the president himself pronounced himself (in favour of) a parliamentary group on the subject. So, 2024 was supposed to have been a watershed year in terms of driving these numbers down, but it turned to the complete opposite,” says John-Allan Namu, editor-in-chief of Africa Uncensored, in a recent social media clip. “It was the worst year on record for women in Kenya.” The new data, showing inter alia that husbands remain the vast majority of perpetrators, can be found here.

In addition to scrutinising the justice system and advocating for more effective protection of women and prosecution of perpetrators by law enforcement, Africa Uncensored argues that the lack of employment and perspectives for Kenya’s male youth is also a contributing factor. The organisation proposes that young men should be the focus of various campaigns and initiatives, including the creation of “opportunities to engage in meaningful work”

On 16 February, John-Allan Namu, editor of Africa Uncensored, will address the challenges of poverty, oppression, and conflict facing Kenya, Africa, and the world at the Nelson Mandela Lecture in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

“Real issues” and “non-issues”

As I stumbled back into the streets, burning tears streaking my face, I was overcome with rage. That moment crystallised the suffocating anger I’ve felt for years—an anger born from trying to survive under a regime intent on squeezing the life out of all of us. While I feared being shot or killed, what was even scarier to me was the thought of living with my dwindling sanity, under a government characterised by insatiable greed and a disregard for human life, choking its people, the country, and our future.

But there was more. I also felt a deep anger toward fellow Kenyans, particularly men, who routinely accuse feminists like me of "distracting" from the so-called "real issues" of the current protest movement, such as rising taxes. This is despite the fact that many women, including feminists, have repeatedly risked their lives confronting the regime precisely over these "real issues." Their criticisms draw from a familiar misogynistic playbook: framing feminists as divisive and undermining the collective struggle. For example, one anti-corruption activist turned political party leader dismissed women's issues as "non-issues" and argued that Kenyans should focus solely on President Ruto's impeachment.

The accusations exposed glaring fractures in solidarity

It is disheartening that some women, including prominent academics, have echoed these sentiments, dismissing gender advocacy as merely an offshoot of “liberal politics.” The term refers to an ideological framework that prioritises individual rights and freedoms, often focusing on personal empowerment while overlooking systemic issues of inequality and oppression. One such academic argued that we should homogenise our identities and dissolve gender differences as the key to solidarity, stating that “liberal politics individualises and atomises, which means it depoliticises.” Yet, it is precisely these accusations that highlight the glaring fractures in solidarity, which continue to weaken collective action in the aftermath of the Finance Bill protests.

Women in resistance

Firstly, these antagonistic perspectives overlook the pivotal contributions of women to liberation struggles—a legacy that today’s feminists in our country continue to uphold. Kenyan women have consistently been at the forefront of resistance, from the Mau Mau movement to contemporary protests. During the Mau Mau resistance against colonial rule, women fought alongside freedom fighters, providing care and sustenance, and enduring shared hardships. In the more recent era of the oppressive Moi dictatorship, Kenyan women and mothers staged a powerful protest in Uhuru Park, demanding the release of their sons, who were political prisoners. Mũkami Kimathi, a freedom fighter and the wife of the prominent Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi, firmly rejected the erasure of women’s roles in these struggles. She described herself as both “wife and mother” to the movement and recounted the profound sacrifices women made. “Women’s bodies were theatres of war … Mau Mau women paid heavily for their real and perceived roles in the war.”

The government fears a united front

In response to the accusations of "divisiveness," I would further argue that the Kenyan government’s hostile reaction to the femicide march reveals its fear of a united societal front. Participants in a previous femicide march in February 2024 made a key observation: occurring prior to the Finance Bill 2024 protests, there was no police violence or state resistance towards the feminists marching at that time. However, the state responded with extreme violence to the recent march, which linked the murders of women to a climate of poor governance and economic hardship.

The brutal violence against this march reflects President Ruto’s increasing recognition of the threat posed by a broad, unified coalition of progressive forces. Ironically, the government’s concurrent establishment of a 100-million-shilling (US$774,514) taskforce to “address femicide” only deepens the suspicion that the government is employing a divide-and-rule strategy. The budget—regardless of the fact that citizens, especially women at risk of murder, or families seeking justice for their slain mothers, sisters, and daughters, will never experience any tangible benefit from this propaganda move—appears to be a deliberate distraction, designed to undermine grassroots organising and further entrench divisions.

Reinvigorating

If the regime itself acknowledges that a united front has the potential to challenge and even defeat them, why can’t we? Given Ruto’s overt violence against the young girls and women who took to the streets of Nairobi, the femicide march should be viewed as a triumph that bolstered the broader “Ruto Must Go” movement, rather than detracting from it. As one Kenyan feminist aptly noted on X (formerly Twitter), “Women have come together and pulled off a massive nationwide protest despite severe repression when we have been unable to pull off mass protests since August.” Countering the critics accusing us of divisiveness, she added: “Yet somehow, this is being seen as a move that will dampen collective struggle instead of reinvigorating it.”

Threatened livelihoods exacerbate violence

The day after the march, still nursing my injuries, I faced an attempted kidnapping by an Uber driver. On my way to a women-only dance party—an event I had been eagerly anticipating for weeks as a much-needed escape from this patriarchal world—the driver demanded that I pay him double the fare, threatening to drive off unless I complied. This was not the first time: Uber drivers had made the same threat to me twice before. It has undoubtedly happened, and is likely happening, to other women as well; often, we have no choice but to pay to be released. This practice illustrates how the recession currently crippling Kenya, with rising taxes and fuel prices that directly threaten men's livelihoods, creates the conditions for gender-based violence to escalate.

Critics of the femicide march overlook the interconnectedness of gender inequality, economic hardship, and systemic governance failures. Socialist feminists have long contended that femicide and gender-based violence are not isolated issues but are deeply rooted in political and economic systems. National debt, unemployment, and underdevelopment shape power dynamics both within households and the public sphere, exacerbating violence against women.

Uncomfortable truths

The fight for justice, therefore, demands more than superficial ‘homogenised’ unity that erases differences and privileges. It requires the courage to confront uncomfortable truths, including complicity in patriarchy, in order to bridge divides and reimagine collective liberation. By embracing an intersectional approach, we can forge alliances that are not only inclusive but also transformative—centring the most marginalised voices and addressing the root causes of oppression. As Kenyan feminist Micere Mugo envisioned, a liberated Kenya is one “where all oppressive institutions are dismantled—politically, socially, for the sake of men and women.” She linked women’s empowerment to African socialism, envisioning a movement that is gendered, youth-centred, and pan-African in scope. This vision sustains my hope for progress in Kenya and for the broader movement striving to achieve it.

- Protests against the Finance Bill, which increased taxes on basic goods while preserving the privileges and luxurious lifestyles of the political elite, rocked Kenya in the latter half of 2024.