In an imaginary interview, composed from actual quotes, the late Zimbawean writer Dambudzo Marechera (1952 – 1987) comments on the troubles his country is facing today.

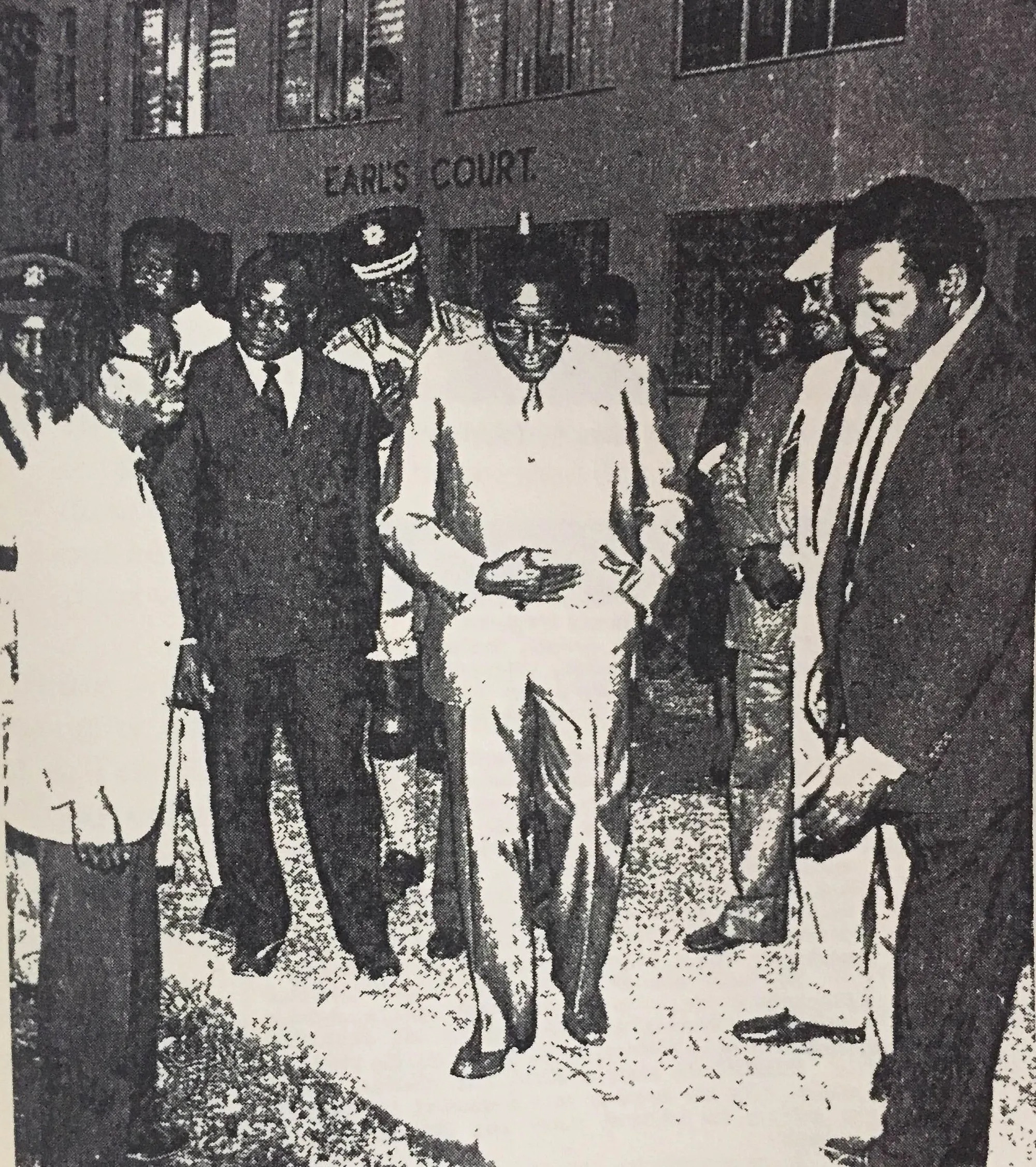

It is reported that in 1978, Dambudzo Marechera, heckled Robert Mugabe when he came to London to address Zimbabweans at the Africa Centre. He had already seen the troubles ahead as he could read through the deceptive characters that were on the brink of leading Zimbabwe. Most of those in power in Zimbabwe today were Marechera’s contemporaries. His award-winning book, The House of Hunger, had just been published. In this imaginary conversation, Tinashe Mushakavanhu finds out what kind of things Marechera would be saying about his country and its endless troubles. What would Dambudzo Marechera be saying is a speculative question that elicits many responses. But here are some of Marechera’s insights extracted from his own books or interviews he gave.*

TM: Where does the problem lie in Zimbabwe? Who is to blame for the crisis in Zimbabwe today?

DM: We in Zimbabwe know who the enemy is. The enemy is just not white, he is also black. The police force, the army in Zimbabwe are three-quarters black. They have always been. And for me…I believe that to see the Zimbabwe struggle as merely a black versus white struggle is stupid and naïve. And hence, in most of my work, there’s always a mistrust of politicians, no matter who they are.

TM: Zimbabwe has been constantly in the news as a kind of hell on earth. What is the actual state of affairs in Zimbabwe?

DM: The rich are getting more powerful and richer and the poor are getting poorer. Any writer worth his name cannot write about that, the publishers are afraid of Government attitude towards anything they publish which may not be considered patriotic.

TM: What is your opinion on the present leadership?

DM: This is a weird world of mechanical speeches; lullabying the povo with mobile horizon promises (what is Zimasset?). They are quick to mend legislation; so the world is what they make it for us who are passive, we who they shamelessly claim to have liberated from the white man. With that as their pretext, they weigh their grievous lot on us day in day out. All we hear are empty slogans.

TM: In the past three decades, the ballot has failed to effect political change. Is it better for Zimbabweans to resort to violence?

DM: I am against everything, against war and those against war, against whatever diminishes the individual’s blind impulse.

TM: What is your comment on the historical domination of Zanu (PF) in post-independence Zimbabwe?

DM: I am afraid of one-party states, especially where you have more slogans than content in terms of policy and its implementation. I have never lived under a one-party state, except under pre-independence Zimbabwe, Ian Smith’s Rhodesia, which was virtually a one-party state. And what I read about one-party states makes me, frankly, terrified.

TM: After 36 years of misrule and dazzling corruption, do you think independence is a reality for the majority, or just an illusion?

DM: I think some things have been improved. But basically our revolution has only changed life for the new black middle class, those who got university degrees overseas during the struggle. For them, independence is a reality; it has changed their income, their housing conditions and so on and so on. But for the working classes and the peasants, it’s still the same hard work, low pay, rough conditions of living. In other words, I don’t think independence so far has really made any significant change as far as the working class are concerned; especially for those who committed themselves to become fighters. They joined ZANLA or ZIPRA before they’d finished their education. Most of them are now unemployed and live in the streets. This is what I wrote about in Mindblast.

TM: Indeed, Mindblast gives a blistering account of the early years of independence. Why do you think Zimbabwe downplayed your significance as a writer?

DM: In some ways there is a certain disconnection between my profession as a writer and the needs of Zimbabwe as a developing country. A developing country doesn’t really need a writer like me. It needs teachers, it needs development officers, it needs people who will help to build a better future for the working class and the peasants. I had come back armed with a profession which is irrelevant to development.

TM: It seems contemporary Zimbabwean writers are uncertain about their stand today. Was it easier for your lot before 1980?

DM: Oh yes, it was. Because the objective was to fight racism and obtain independence. After UDI in 1965 Ian Smith deliberately created the Rhodesia Literature Bureau to promote a certain kind of Shona and Ndebele literature which would be used in the schools and perpetuate the idea that racism is for the good of the blacks. And we had writers who were writing the very books Ian Smith wanted the blacks to read. In primary school I was taught Shona literature which caricatures black people and which was in line with the specific political policies before independence. One of the main themes in Shona literature of that period was the story about a person coming from the rural areas thinking that he’d have a good life in the city. Then he or she comes to the city and goes through hardship and decides to go back to the rural areas because that’s where heaven is. Now this was in direct line with the urban influx control policy. Blacks were being discouraged by the city council and by the government to come to the cities.

In other words, even before I left the country, the literature which was being written here had no relevance to me or even to our people, to those who knew. Before independence you had two schools of thought among writers: those who participated in Ian Smith’s propaganda programme, and those who had to run into exile and write protest literature. You will find that after independence the ones who were in the first school are now the ones in high positions, and those who were part of the Zimbabwean protest literature are the ones who are having problems or who have been forced to compromise themselves. Literature is now seen merely as another instrument of official policy and therefore the writer should not practise art for art’s sake or write like Franz Kafka or like James Joyce or explore the subconscious of our new society. All that is for European bourgeois literature. And that’s why for instance my work is condemned. One of the reasons given by the censorship board when they banned Black Sunlight on August 7th, 1981, before I had come back, was that Dambudzo Marechera is trying to be European, that this book has got no relevance to the development of the Zimbabwean nation.

TM: The economic downturn has driven many people out of the country, though in your own case what drove you out of the country was the political madness of the time. Tell me, when you came back after years of exile in Britain, what kind of country did you expect?

DM: The only idea I had of what to expect was what I had been reading in the British press about the struggle here and about what was going on in Uganda, about the military coups in Nigeria and so on and so on. In other words, the idea that our own independence would be another disaster had been instilled in me very much. The first time I heard the Prime Minister's motorcade, and there were suddenly all these sirens going, “whee, whee, whee”, I thought, “shit, another civil war has started.” And I rushed to my hotel room and just locked the door, listening hard, waiting for the gunfire. Some people here call the motorcade ‘Bob and his Wailers,’ after Bob Marley.

TM: The Third Chimurenga came up with a wholly new cultural programme meant to celebrate Mugabe the supreme leader, first secretary of ZANU PF, commander of defence forces, chancellor of all universities through musical galas, political jingles, etc. What in your view is the relationship between culture and politics?

DM: Here we have a deliberate campaign to promote Zimbabwean culture: everyone is talking about it, building it, developing it. When politicians talk about culture, one had better pack one’s rucksack and run, because it means the beginning of unofficial censorship…. When culture is emphasised in such a nationalistic way that can lead to fascism. When in Nazi Germany culture started to be defined in a nationalistic way, it meant that all other people, all other nations were stupid; it meant intellectuals, painters, writers, lecturers, being persecuted or being assassinated. In this sense, all nationalism always frightens me, because it means the products of your own mind are now being segregated into official and unofficial categories, and that only the officially admired works must be seen. All the other work we must hide or tear up.

*All the responses are actual quotes from Dambudzo Marechera.

Tinashe Mushakavanhu is a Junior Research Fellow in African & Comparative Literature at the Oxford Comparative Criticism and Translation (OCCT), St Anne's College. He holds a PhD in English from University of Kent (England) and completed postdoctoral work at University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa). He has an interest in literary archives from southern Africa and interrogates issues to do with literary legacies. Apart from writing journal articles, book chapters, this work also manifests through a series of creative publications, exhibitions and digital humanities projects.

This article was first published by Medium.com. Another version of the interview is published in Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats (Black Chalk & Co. 2019).