“The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

Milan Kundera

Not forgetting is living, and living is not forgetting. The world's attention was focused on 9/11 when the ruler of Eritrea, President Isaias Afwerki — in power for 33 years without elections — struck hard against critics and independent media. On September 18, 2001, and in the weeks that followed, he arrested all critical members of parliament, ministers, and generals. They had asked the president to implement the country’s first constitution, ratified in 1997, and to account for the “border war” (1998-2000) with Ethiopia, which had taken the lives of approximately 100,000 Ethiopians and Eritreans.

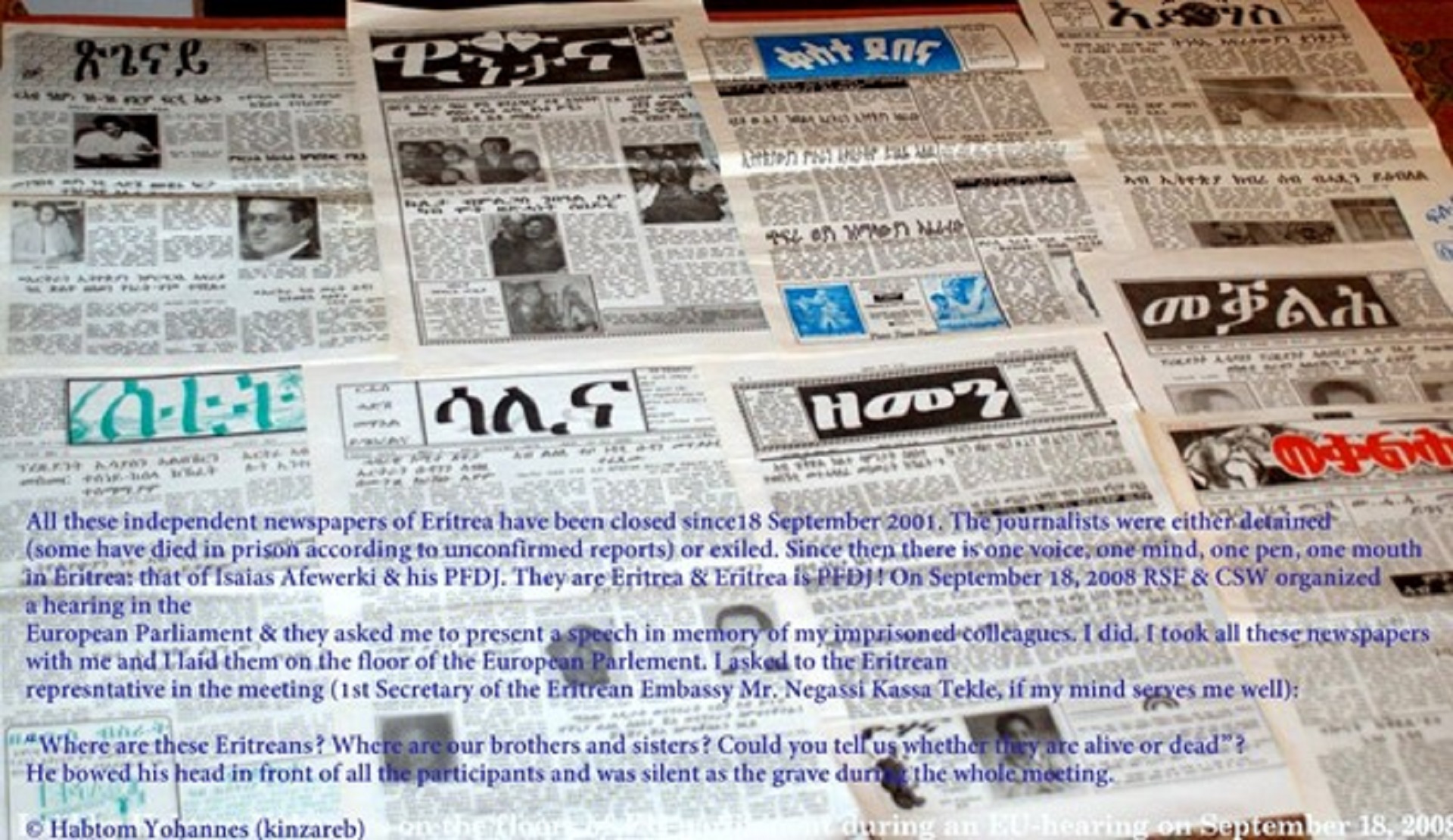

State media did not give Afwerki’s opponents a platform to tell their stories, but emerging independent newspapers published extensive interviews with photos of these critics hated by the regime. In retaliation, Afwerki shut down all independent media and made independent journalists disappear along with the critics. 23 years later, we still don’t know where the critics and journalists are, or whether they are still alive. Their parents, wives, and children have been suffering immensely ever since.

Arrests and disappearances without due process have become commonplace in the 33 years that Eritrea has existed as an independent country. A few months before the arrests in 2001, I was in Eritrea for the Dutch Radio1 program De Ochtenden, and I spoke with some of the critics of the regime about the difficult situation in which they had to work. For example, they regularly had to report to a special department of the Ministry of Information and Culture to account for publications that were not favorable to the regime, and to reveal their sources. But no one had expected the permanent closure of all independent media, nor the mass abduction of journalists and critics. Initially, there was great public outrage both within Eritrea and internationally. All EU ambassadors temporarily left Eritrea in protest. But over the years, these prisoners of conscience and their families, who suffer with them outside the prison, seem to have been forgotten.

As long as my memory works and I am privileged to live in a country with the freedom to remember who you want to remember, to think what you want to think, and to publish what you want to publish, I have decided not to forget them. Writing about them and inquiring about their fate has cost me and my family dearly. Since 1998, the long arm of the regime has tried to silence me in the Netherlands. Threats are commonplace. For 23 years now, I have been trying in various ways to keep the names and stories of the prisoners of conscience alive.

Through this article, I call on the Dutch media, human rights organisations, the Dutch public, and the Dutch government not to forget the prisoners of conscience and their family members. It would be wonderful if every media outlet in the Netherlands could post a photo with the names of these victims on September 18 and do so every year until they are released.

In one of his most reflective prose works, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, the Czech exile, the late Milan Kundera, has a certain politically active character, Mirek, say: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting,” after experiencing firsthand how government agents pursued him into his memory to erase him and his loved ones from history. After the arrests of the Eritrean prisoners of conscience, the Eritrean regime meticulously worked to erase all memory of them. Journalism is, par excellence, the memory of society. It archives and connects the present with the past. It holds up a mirror to society, in order to call those in power to account. The Eritrean Ministry of Information and Culture purged all media and other “memory keepers” that could confront those in power, and labelled them “enemies of the state.”

In the Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders and other press freedom indicators, Eritrea has been at the bottom for decades. Mentioning the names of the disappeared prisoners of conscience or showing sympathy for them or their family members is considered a crime in the eyes of the regime. People are even arrested on suspicion of thinking about leaving the country illegally. In 2008, I was a guest at the European Parliament during a hearing on the prisoners of conscience in Eritrea. The current Eritrean ambassador to the EU and the Netherlands, Mr Negassie Kassa Tekle, was present. I laid down all nine independent newspapers of Eritrea on the floor of the European Parliament and asked the ambassador, then Consul-General: “Where are all the prisoners of conscience of Eritrea? Where are the journalists? When will they be tried? And when will these newspapers be allowed to reappear?” He covered his bowed head with both hands and remained silent. The silence, the impenetrable bars surrounding the prisoners, continues, and Mr Kassa Tekle has since been promoted to ambassador, after the former ambassador, Dr Tesfay Ghirmatsion, turned his back on the regime with a note on the table: “I no longer find it responsible to continue serving such a regime.”

He covered his bowed head with both hands and remained silent. The silence, the impenetrable bars surrounding the prisoners, continues, and Mr Kassa Tekle has since been promoted to ambassador, after the former ambassador, Dr Tesfay Ghirmatsion, turned his back on the regime with a note on the table: “I no longer find it responsible to continue serving such a regime.”

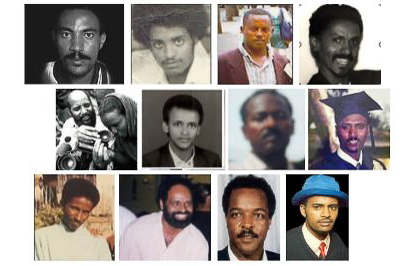

Who are the journalists who, in September 2024, have been languishing in isolation in Eritrean prisons for 23 years? Below are their photos with short bios. This list is not exhaustive, as the arrest of writers, state journalists, critics, believers, and conscientious objectors continues. The Netherlands, home to 18 million people, has 48 prisons, while Eritrea, home to about 4 million people, has more than 60.

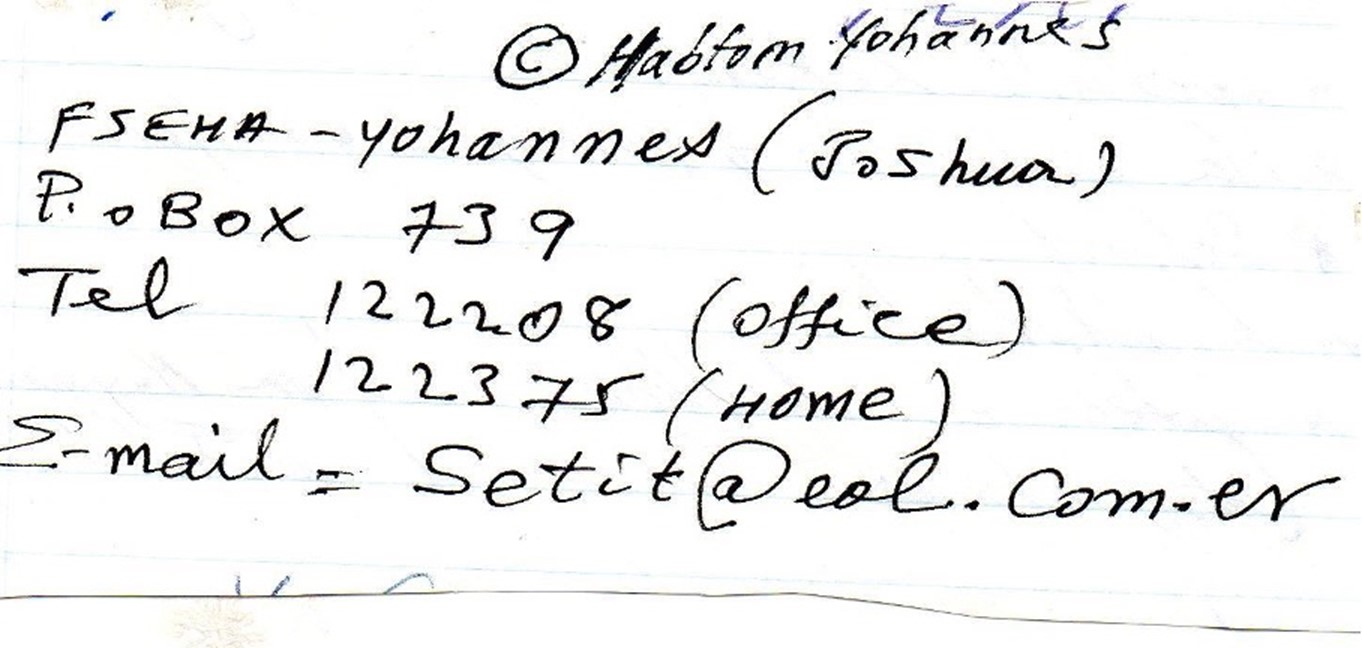

Fessehaye Yohannes (Joshua), would have turned 68 this year. He was 45 years old when he was arrested. He has three children. He was a former comrade of Eritrean dictator Isaias Afwerki, but Afwerki denied knowing him. He was the co-founder of the newspaper Setit, a playwright, and also a founder of a children's theater. We have heard that he died in prison. In 2010, on World Press Freedom Day, I wrote this letter to Joshua in De Volkskrant. I still keep his business card, which he wrote himself, as a memory.

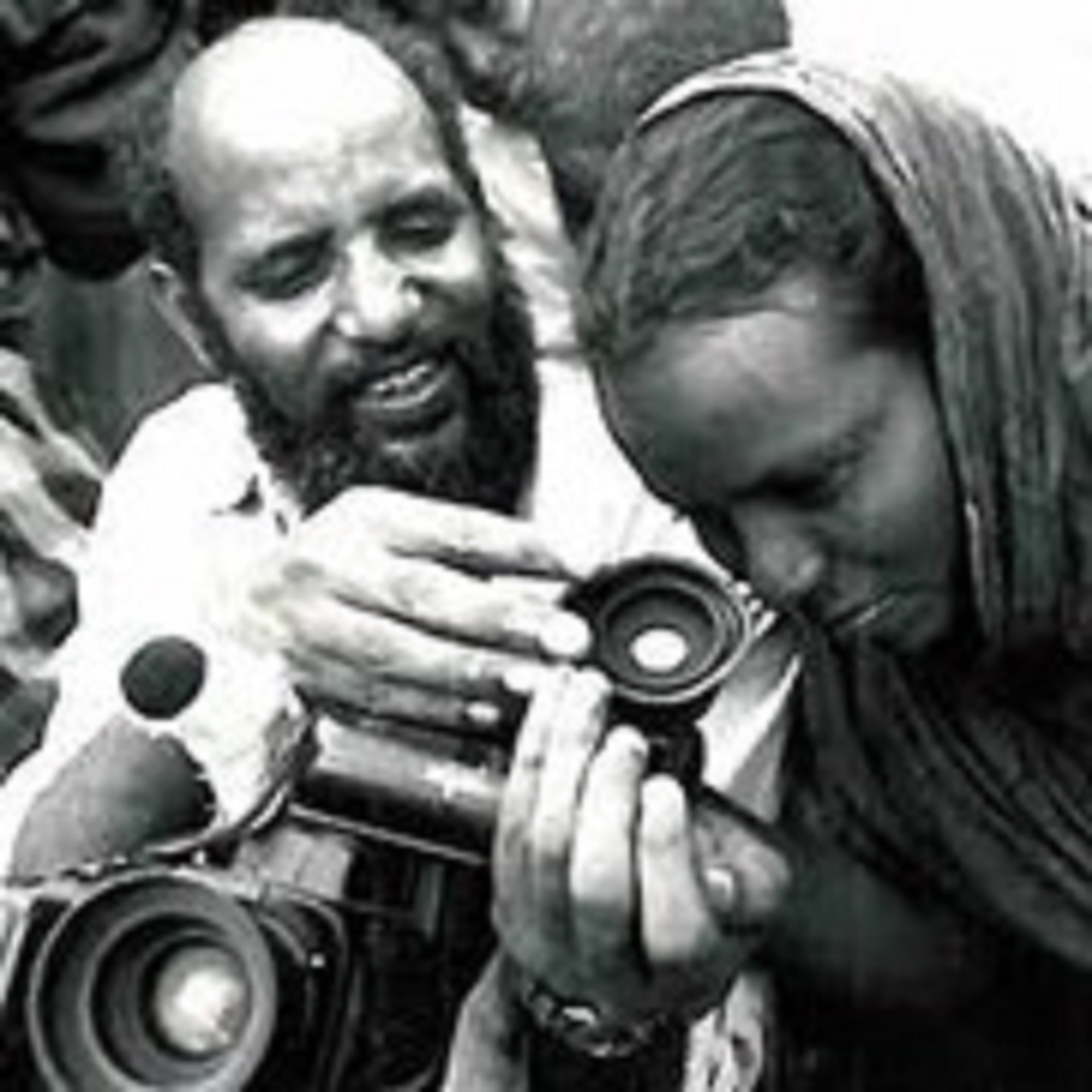

Seyoum Tsehaye was also a former fighter and comrade of the president. After independence, he was a co-founder and head of the state radio station Voice of the Masses and state television Eri-TV (radio and television have always been in government hands). He was also a freelance journalist and cameraman for the independent newspaper Setit. He has two daughters: Abie and Belula. Belula was in the womb and Abie was two years old when Seyoum was abducted. In 2013, Abie made an emotional plea to the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva: “Please ask the Eritrean authorities to give us our parents back.” Like many families of prisoners of conscience, Seyoum Tsehaye's family has fled Eritrea.

Yousuf Mohamed Ali was the editor-in-chief of the newspaper Tsigenai. He was the first among the independent newspapers to publish an interview with then Vice-President Ahmed Mohamed (Sherifo), in which the he openly criticized the Eritrean president and his refusal to hold meetings and implement the constitution. This cost him dearly. Like many of his colleagues, Mohamed Ali was arrested in September 2001 and has been missing ever since. According to some sources, he died in 2003 in the high-security prison Eila-Eiro. No one knows if this is true or where he may be buried.

Seid Abdulkadir was the editor-in-chief of the newspaper Hadas-Admas. He was arrested on September 23, 2001. It is believed that he died in the high-security Eila-Eiro prison. This prison was specially built for the “Group of 15,” as the arrested critical officials – ministers, generals, and members of parliament – are called, and for the independent journalists. No one can confirm who is still alive and who has passed away.

Mattewos Habteab (53) was 30 when he was arrested. Mattewos, or Matu, as his friends and colleagues called him, was the founder and editor-in-chief of Meqaleh (Echo). A graduate in mathematics from the now-closed University of Asmara, he combined journalism with teaching until his arrest in September 2001. There are also conflicting reports about him. It is possible that he has died in one of the hundreds of secret prisons scattered across the country.

Dawit Habtemichael (53) was also 30 when he was arrested at the school where he taught physics part-time. He had also graduated from the University of Asmara. Dawit was one of the co-founders of Meqaleh (Echo) and the deputy editor-in-chief. His father (80), who was also a physics teacher, lives as a refugee in the United States and still feels guilty for having encouraged him to leave his hiding place and start teaching. No one knows where Dawit is or if he is even still alive.

Hamid Mohammed Saeed worked for the state television channel Eri-TV. He was an Arabic editor for news and sports. He was arrested in May 2002. No one knows where he is or if he is still alive.

Amanuel Asrat (54) was a poet and journalist for the newspaper Zemen. At the time of his arrest in September 2001, he was the editor-in-chief. In his poems, he criticized wars, as seen in The Sin of War:“the ugliness of the thing of war, when it springs comes, when its ravaging echoes knock at your door, it is then that the scourge of war brews doom, But… you serve it willy-nilly, unwillingly you keep it company, Still, for it to mute how hard you pray.”

On January 14, 2016, he received the Oxfam Novib/PEN Award for Freedom of Expression along with Egyptian writer Omar Hazek and Turkish journalist, author, and filmmaker Can Dundar. This is also a crime in the eyes of the Eritrean regime; I was honored to accept the award on behalf of the family and to bring it to them. His parents and siblings live in exile. His elderly parents, with failing health, live in Germany, holding onto hope and fear regarding the fate of their eldest son.

Dawit Isaac (1964) was a co-owner and journalist for the newspaper Setit. Dawit, who held Swedish-Eritrean nationality, lived with his wife and three children in Sweden before returning to Eritrea to work as a journalist. His wife and children still live in Sweden, waiting for any sign of life from their loved one. In 2011, Swedish journalist Donald Boström interviewed President Isaias Afwerki about Dawit Isaac: “We do not see him as a Swede. He is an Eritrean. He is compromised for working for European and American intelligence services. We will not release him, but we will not prosecute him either. We know how to deal with him and people like him.” The Swedes and Finns have attempted to secure Dawit Isaac’s release, but to no avail. The city of Malmö named its “Freedom of Expression Library” after Dawit Isaac in September 2020, and in 2009 he received the Sakharov Prize from the European Parliament.

Jmie Kmeil was also a comrade of the Eritrean president during the Eritrean independence struggle. Jmie worked for the Arab state newspaper Eritrea al-Hadeetha, among other roles as a sports journalist. He was arrested on November 24, 2005. In 2016, still unverified reports surfaced that Jmie, along with four other prisoners, was extrajudicially executed on the night of August 22-23, 2007.

Medhane Haile Afle (56) was 33 years old when he was abducted by the security services of the Eritrean regime. He studied law at the now-closed University of Asmara. Afterwards, he worked for the newspaper Keste-Demena (Rainbow), where he was also the deputy editor-in-chief. Every time I met him, I could read from his face how worried and restless he was.

Temesgen Ghebreyesus (1965) was an actor and journalist for the newspaper Keste-Demena (Rainbow). Temesgen was born and raised in one of the neighborhoods of Asmara, Geza-Berhanu. He was the sports journalist for the newspaper and also worked as an actor, comedian, and cameraman. He was married to actress Kibra Tzegay, and together they had a son, Nahom. Temesgen was also arrested in September 2001. For 23 years, no one has known which prison Temesgen is held in or his condition. He may have also passed away and been secretly buried.

Sahle Tsegezeab is known to many by his nickname "Wedi-Itaay" (the son of the nun). Sahle was also a comrade of the president during Eritrea's independence struggle. He was arrested in October 2001. His articles appeared in various independent newspapers. Sahle criticized the delay in the implementation of the constitution in his articles. He also worked as the head of civil affairs for the chief prosecutor in the capital, Asmara.

Saleh Idris Sa’ad (Jazairy) was a journalist for the Arabic state newspaper Eritrea al Hadeetha (New Eritrea). He was arrested in 2002. No one knows where he is or if he is still alive.

Zemenfes Haile was a journalist for the newspaper Tsigenay. There are conflicting reports about his possible release, but due to the lack of freedom of expression and press freedom, they are still impossible to verify. The regime seems to benefit from a deafening silence about arrests and releases. A source told me that in Eritrea, people are arrested and sometimes released in turn. After that, there is no guarantee when or if you will be arrested again.

These well-known journalists are representative of all the tens of thousands of prisoners of conscience in Eritrea. I view freedom of the press as the thermometer for all freedoms in society. After the closure of independent media and the arrest of all independent journalists, Eritrea has turned into a desert of information. No one knows who, when, or where someone will be arrested until a family member dares to report the disappearance. People fear that their loved ones will be further tortured if they communicate their disappearance to the outside world. The silence of the populace has reinforced the regime in its ruthlessness. That silence begins with the killing of independent journalism. They are not allowed to speak, but we are. They are not allowed to name their missing loved ones, but we are.

If it were up to the regime, I would not be allowed to be a journalist in the Netherlands. I have obtained confidential secret documents from Eritrea which show that the Eritrean regime is monitoring my activities here in the Netherlands. Everything I write or say in the Dutch media is translated and sent to the security services in Eritrea. The secret documents, stamped by the Eritrean consulate in The Hague, state: “Our supporters in the Netherlands write and call us about journalist Habtom Yohannes. They request the Eritrean government to take measures against him, and if this does not happen, the regime’s supporters will take action themselves.” I could have been one of the disappeared journalists. As long as I have freedom, I will not remain silent for the sake of free speech and on behalf of the prisoners of conscience who have been silenced.

About the author.

Habtom Yohannes is a Dutch journalist and researcher at Radboud University. He is of Eritrean descent. Habtom is a co-author of Eritrea's first constitution from 1997. He provided advice on the country's media law in 1996. Based on that law, nine independent newspapers were established. These operated with ups and downs until their closure in 2001 and the arrest of all independent journalists. Some of the independent journalists fled the country. Habtom is the winner of the very first edition of the Golden Brick, a new Dutch journalistic award for "engaged journalism" presented by the Christian College of Journalism in Ede.