A transnational investigation in Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Uganda, Kenya and the DRC by the African Investigative Publishing Collective

Kenya chapter

Nairobi, March 2017

They had come, way back in the year 2000, to promise Lucianna Wanjiku, 58, that her mud shack in Soweto settlement in Kibera, Nairobi, -often called ‘the greatest slum on earth- would be rehabilitated. She would get a title deed to the piece of land on which her single-room was built, the government men had said. She had forked out Sh1,000 (US$ 10) she had saved over five years as a down-payment. They had written a number on her door, saying it corresponded to the title deed. Though the number has long since faded, she recalls it, seventeen years later, still. “KS/SD/57. I think it meant ‘robbery.’ Because these men disappeared with my money.”

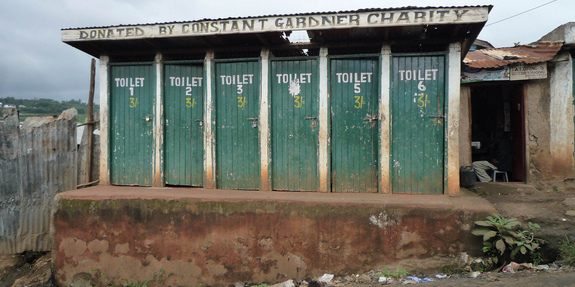

Soweto, where Wanjiku lives with her five children, in a single room shack, is an informal village at the southern tip of Kibera. Here, rivers of raw sewage snake through the landscape of dilapidated mud-walled tin houses. Only one in five has electricity. The cost of water, a scarce commodity, is ten times its market price. As many as 4,000 people share a rickety toilet. Security is provided by vigilantes. That is because this informal village is officially an illegal settlement. Which means that neither the government nor the so-called slum-lords (the shadowy figures who own the shacks) are obliged to provide any services, such as water and sewage, to those who live here.

Soweto has been earmarked for development since the mid-seventies, when it was a relocation site for a housing project in adjacent Langata in the mid-1970s. But the newly built suburb ended up benefiting the middle class -those who could pay the gentrified high rents- and not the wretched lives displaced by the development. Wanjiku was there, then, too: she remembers vividly how she was removed from Langata in 1970s to give way for her first “low income housing scheme. “Hundreds of us moved out yet only one of us, the civic leader, managed to secure a house there.” Agitated, she gestures in the direction of the Soweto Highrise Scheme, hundreds of magnificent flats, separated from ‘her’ Soweto by a tattered road, which was once tarmacked but has been gradually swallowed by neglect. “All those buildings belong to us but were taken over by the rich people, driving big cars. Now we are their labourers.”

“Fraud at the hands of the government”

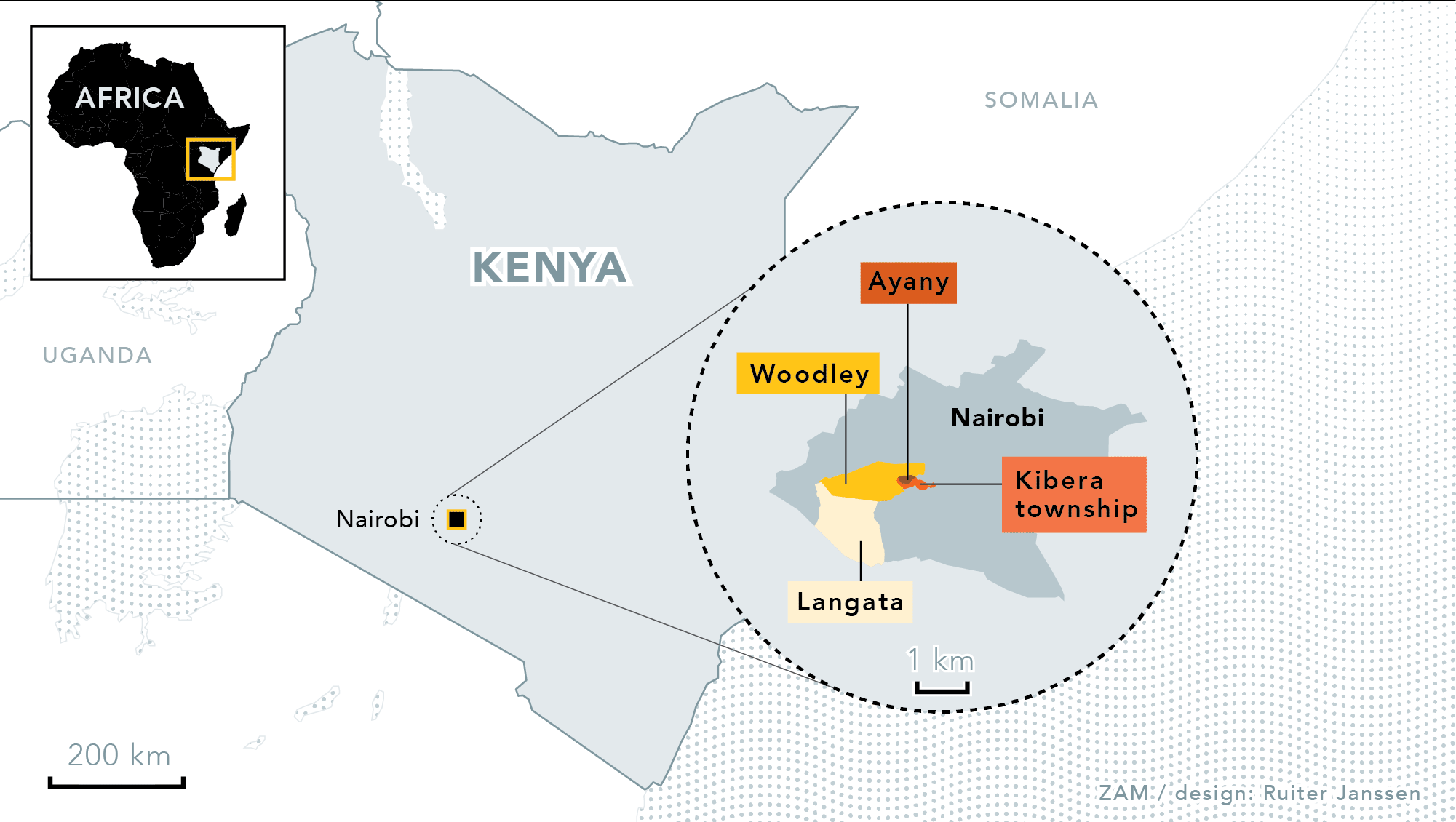

It has happened so many times: once-upgraded Moroto turned into a commercial site; Pumwani became rich and its original slumlords simply took hold of another muddy place. Ayany, parts of Woodley, Kibera Highrise, Langata. All these places, earmarked to benefit Kibera dwellers who generally live on less than US$ 1 a day, are places for the middle class now. The poor have been continuously removed, relocated, cut off from whatever social networks and means and ways that they had themselves built to survive, invariably to end up in the mud again elsewhere.

When the men came back in 2007, again promising improvement, Wanjiku sent them away. “I don’t want them. This is a fraud at the hands of the government.” The shack, where a wooden table is sandwiched between the bed, three jerry-cans and two seats -at night all heaped together to create sleeping space- , has no place to cook. Food is prepared outside, in the open. There is no running water, no electricity. “The six of us sleep here. My two daughters and I share the bed. My 25 year old son and the others sleep on the floor.” Wanjiku rummages around behind a dirty cloth curtain in the corner and finds the paper which, she says, is the receipt she got for the Sh1,000 payment. She has kept it for seventeen years. Just as a reminder. “This project they are talking about is going to rob us again.”

She is not wrong. The current US$13 billion Kenya Slums Upgrading Project (KENSUP) funded by the UN Habitat and the World Bank, like the previous upgrading projects, is already once again displacing area residents in favour of the wealthy.

A parking full of cars

KENSUP’s aim, according to a UN Habitat strategy document, is “to improve the livelihoods of people in Kenya’s slums through provision of security of tenure, housing improvement, income generation and physical and social infrastructure”. The 15-year KENSUP scheme was expected to improve the livelihood of 5.3 million urban slum dwellers by 2020. It involved the construction of 45,000 house units annually. The first phase is again targeting Soweto, where Lucianna Wanjiku lives: one of Kibera’s 17 villages. It is there that KENSUP is supposed to deliver 770 housing units at Sh 650 million (US$ 6,6 million), together with physical and commercial infrastructure and sanitation, among other things. The project is part of the UN’s Slum Upgrading Programme that, and in line with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is meant to uplift conditions of life in poor countries.

“Slum upgrade” is Millennium Goal 7, Target 11, “which aims to significantly improve the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers by the year 2020,” said Ann Tibaijuka, the UN Habitat boss at the time of the launch of KENSUP in 2005. Tibaijuka said she believed that the success of Kibera project could have far-reaching implications with regard to the replication of the scheme elsewhere in Africa.

But, again, it is not happening that way.

“They were meant to be our houses but they were taken over by outsiders,” Soweto resident Richard Wafula says, pointing to a vista of 624 high-rise apartments on the fringes of the township, developed under KENSUP in 2007. The neighbourhood playgrounds are all full of cars belonging to those who live there now. ““We applied but never got any because they very expensive. The rich grabbed them.” The settlement is also called Soweto, but it is, once again, a newer, better, Soweto. Nearly all the tenants and owners of the new apartments are from outside Kibera. They are middle-class bureaucrats, politicians, businesspeople and representatives of NGOs.

KENSUP also didn’t deliver anywhere near the planned 45 000 ‘units annually.’ By 2015, only the afore mentioned 624 apartments were completed in Soweto East Zone A, 17 years since the government and UN Habitat signed their MoU in 2003. Officially, KENSUP officials have given explanations for the delays. But unofficially, sources say the KENSUP target has been moved from 2010 to 2025. Few feel that it will perform better in the next eight years.

Firstly, the slum population keeps growing. Secondly, houses are useless to the poor without land tenure, security and infrastructure. Resident Michael Arunga, who represented Kibera civil society in the KENSUP planning committee, feels that the project was doomed from the start. “How can people without any income even afford decent housing? People have no livelihood.” He believes the scheme was started for “political reasons” and not genuine in assisting Kibera people to build better lives. Some former Kibera residents who did move in the new houses now sub-let them in order to make a living, he says, and still stay in shacks.

The slum lords don’t want to let go of their properties

Researcher Peter Mwaura Karani, who carried out a small survey about KENSUP among Kibera residents in the context of slum upgrading research he did for the German University of Magdeburg (1), found that 27 out of 33 respondents believed the upgrading programme would fail. They feared displacement, affordability of high rent, forced relocation which could affect meagre livelihoods, and a destructive effect on social life. “The slum problems are too diverse to be tackled by simplistic approaches,” Mwaura Karani says. “The way it is now, it is just complex, confusing and a time-bomb.” This is mainly, he and other observers say, because Kibera residents themselves were not asked for their views -or, in the case of Michael Arunga, were not listened to. “We have been telling the Department of Housing that they should involve people. If they don’t, it’s going to be chaos,” Jack Makau, an official of the NGO Slum Dwellers International, says.

Meanwhile, neither the government nor UN Habitat talk about the elephant in the room: the slum lords, these powerful “shadowy” individuals who own the makeshift houses but who stay in affluent estates elsewhere. They do not want to let go of their properties. Raking in the rent, they will also benefit when it is time to be paid compensation in case of relocation or demolition, since they are the actual owners of the houses. After which they would buy up more places to rent out, all the while never bearing any responsibility for the sewage-flooded area itself.

Recent research by the World Bank as reported in the Kenyan press (2) has suggested a solution could lie in bailing out the slumlords once and for all. The World Bank report calculates that US$ 1 billion would suffice to make landlords go away and give residents real tenure, after which real upgrading could take place. But that is not happening. Instead, government plans to pump another US$ 5 billion into KENSUP.

Sweet bread

Lucianna Wanjku will have no more of it. She may live in a shack in the mud, but it is her life, and she will rather stay here, she says, than be toyed with. The kitchen knife firm in her hand, she slices through the air, as if attacking an imaginary enemy. With half her hair not plaited, her eyes sunken in their sockets, and her skeleton too thin for her 58 years, her young grandson in the corner of the shack giggles at her agitation. Who is this? The child asks. I giggle, too. “Come here boy, these are good visitors, they bring with them good things.” “Bread,” the child inquires, stealing a glance at my side. “Today we will eat bread?” Yes, says the grandmother. Sweet bread, yes.”

We talk, still, about hopes for the future, real upgrades perhaps. But it is clear that Wanjiku would need to see before she believes, otherwise she will just remain where she is. “I have lived like this all my life. I married here, got my first born here. They got educated here. We are used to these conditions; we have been happy. We do not want to leave this place.”

The ‘upgrading’ plans continue, though. A formal spokesman for the housing ministry said that tenure and infrastructure services were now on the agenda and that 498 informal settlements had already been “mapped out” for that purpose. He also called KENSUP a “huge success.” But a top official in the same ministry, requesting anonymity, had another view. “I don’t think people high in the government want Kibera to cease existing. They own the place and make so much money from the slum.” +  THE BIGGEST SLUM (but not really)Many NGOs estimate Kibera’s population as over a million. It is probably around 200 000, but, in the words of a former official of the NGO WorldWatch in 2010, “the inflated figures were useful to NGOs ( ) to shock charities into donating more money (2) www.nation.co.ke/oped/Opinion/-/440808/1009446/-/nyf5o7z/-/index.html. A 2011 Columbia Journalism Review article claimed that “6,000 or more NGOs were working in Kibera http://archives.cjr.org/reports/hiding_the_real_africa.php.” That would be one NGO per 30 people. http://cameroon.openspending.org/en/pib.html#/~/total All this just to attract donor funding for the politically-connected? Yes, said the official: “The real intention of authorities in the slum upgrade is to milk Kibera dry and sustain its misery.”

THE BIGGEST SLUM (but not really)Many NGOs estimate Kibera’s population as over a million. It is probably around 200 000, but, in the words of a former official of the NGO WorldWatch in 2010, “the inflated figures were useful to NGOs ( ) to shock charities into donating more money (2) www.nation.co.ke/oped/Opinion/-/440808/1009446/-/nyf5o7z/-/index.html. A 2011 Columbia Journalism Review article claimed that “6,000 or more NGOs were working in Kibera http://archives.cjr.org/reports/hiding_the_real_africa.php.” That would be one NGO per 30 people. http://cameroon.openspending.org/en/pib.html#/~/total All this just to attract donor funding for the politically-connected? Yes, said the official: “The real intention of authorities in the slum upgrade is to milk Kibera dry and sustain its misery.”

All this just to attract donor funding for the politically-connected? Yes, said the official: “The real intention of authorities in the slum upgrade is to milk Kibera dry and sustain its misery.”

Click here for the other country reports: Cameroon, DRC, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Uganda

- www.isoz.ovgu.de/isoz_media/downloads/arbeitsberichte/56.pdf

- www.capitalfm.co.ke/business/2017/02/converting-kibera-slums-formal-settlement-inject-sh100bn-nairobi-report/; www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2017/02/09/world-bank-report-improving-conditions-for-people-and-businesses-in-africas-cities-is-key-to-growth and https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25896