Lack of state services and protection encourages despair and militancy

The reason why Somali soldier Ali (20) is seriously thinking about joining the ‘terrorists’ of Al-Shabab who are waging a violent insurgency in his country, often with terrorist methods, is that he doesn’t get a salary from his government. He hasn’t had for months. “We don’t even get weapons. The government is not committed to us in this war. It would be easier for me to be with the ‘boys,’” -common jargon for Al-Shabab, ed.-, he says as we meet him, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, his uniform dirty, at a roadblock on our way to the partly Al-Shabab controlled Middle Shabelle region. “My parents live close by here. If I joined the boys, I could at least visit them without getting killed.”

A transnational investigation by the African Investigative Publishing Collective (AIPC) into state capability in six African countries has shown that state neglect and wastage of budgets for citizens’ services lead to despair, alienation and in worst cases to young men taking up arms against governments. In Somalia, team member Muno Gedi interviewed several soldiers who either considered joining the ‘terrorists’ or already had done so. This was not because they agreed with the insurgents but because they felt that the government had abandoned them.

Al-Shabab is not good but at least I will not live with fear

In contrast, militants were seen as more “organised.” “Al-Shabab is not good but at least I will not live with fear,” one soldier called Abdinur (27), interviewed at an army camp in Middle Shabelle, said. A number of interviewees higher up the ranks in the army, among whom Abdi, a deputy commander at a batallion in the capital Mogadishu and a source at the Somali National Intelligence Agency (NISA), expressed scorn about the government, saying they were aware that the army receives millions in support from donor countries, but that only the “president and the prime minister know where it goes” and that the money was used for “their private projects.”

One former Somali National Army soldier in Middle Shabelle who recently joined the insurgents, was found looking well-dressed in blue shirt and dark green trousers. He said he was much happier since he had deserted. “All the safest places are under the control of Al-Shabab. It is only here that I can be safe and get a little salary,” he said, adding that he “had lost his two best friends because the government won’t give us equipment.”

Usual godfathers

The transnational team found that state neglect and disservice were also a factor in militancy and insurgency in West African Mali and Cameroon. In Cameroon, an armed insurgency aimed at independence in the western region has recently emerged after years of neglect by a central government. Team member Chief Bisong Etahoben, who reported in Cameroon, traced a set of state projects meant to assist citizens that had been bankrupted by the government in the past twenty years. These included an agricultural grains development project that had according to previous staff members paid for ruling party officials’ “voyages, weddings and baptisms”; the national airline (where, also in the words of previous staff members, ‘usual godfathers’ had “given all the jobs to unskilled relatives” and “helped themselves to free air tickets for themselves and their families,”) as well as two rural farmers’ loans schemes. In the latter case, according to a senior official in the Finance Ministry who spoke to Chief Etahoben, “ government and ruling party officials had borrowed large sums of money knowing they would never pay back.” Very recently, Cameroon also lost the opportunity to host the African Cup of Nations after budgets for stadiums and hotels had been spent without delivering the needed infrastructure.

Children only receive three spoons of porridge every other day

In Mali, meanwhile, a school meal programme specifically designed to keep children in school and away from armed militias who recruit among the unemployed population (1), is failing all around. Teacher Ousmane Dicko, interviewed by reporter David Dembélé in one of the deprived schools in north-eastern Youwarou, where children only receive three spoons of porridge every other day, said that “schools were even closing” since “the municipality keeps half of the grain for itself.” The mother of Samerou, a 12 year old boy in Douentza in Mali’s north despaired about the future of her son if he remained uneducated but said he was simply too hungry to “go and also find no food at school.”

Interviewed locals and school teachers in three different regions of Mali pointed at local government officials keeping the money and food or selling it for their own accounts, instead of distributing it to the schools. Trying to trace budgets and food, Dembélé found that regional state officials were unwilling to answer any questions about the disappearances, while no control at all was exercised by the central administration over the distribution of the budgets and the food. The National Centre for School Canteens (CNCS), which officially manages the programme, told Dembélé that “they don’t track” food or money. Dembélé also could not find anyone in the education department who knew how much food was being bought or distributed to schools. Meanwhile, the CEO of the CNCS, Sarmoye Boussanga, a man known for his loyalty to the country’s president, insisted that all was working well.

Despair

In Kenya, the transnational team found no militancy but despair as they interviewed patients who were unable to pay for needed medical care. Esther Wambui, a patient at the Kenyatta Hospital in Nairobi, told team member Joy Kirigia that she could not afford chemotherapy treatment for her cervical cancer. Wambui’s sister Gladys Mwihaki, who makes four US$ a day as a washer woman, told Kirigia that “all Esther does is cry all night and we just don’t have the money.”

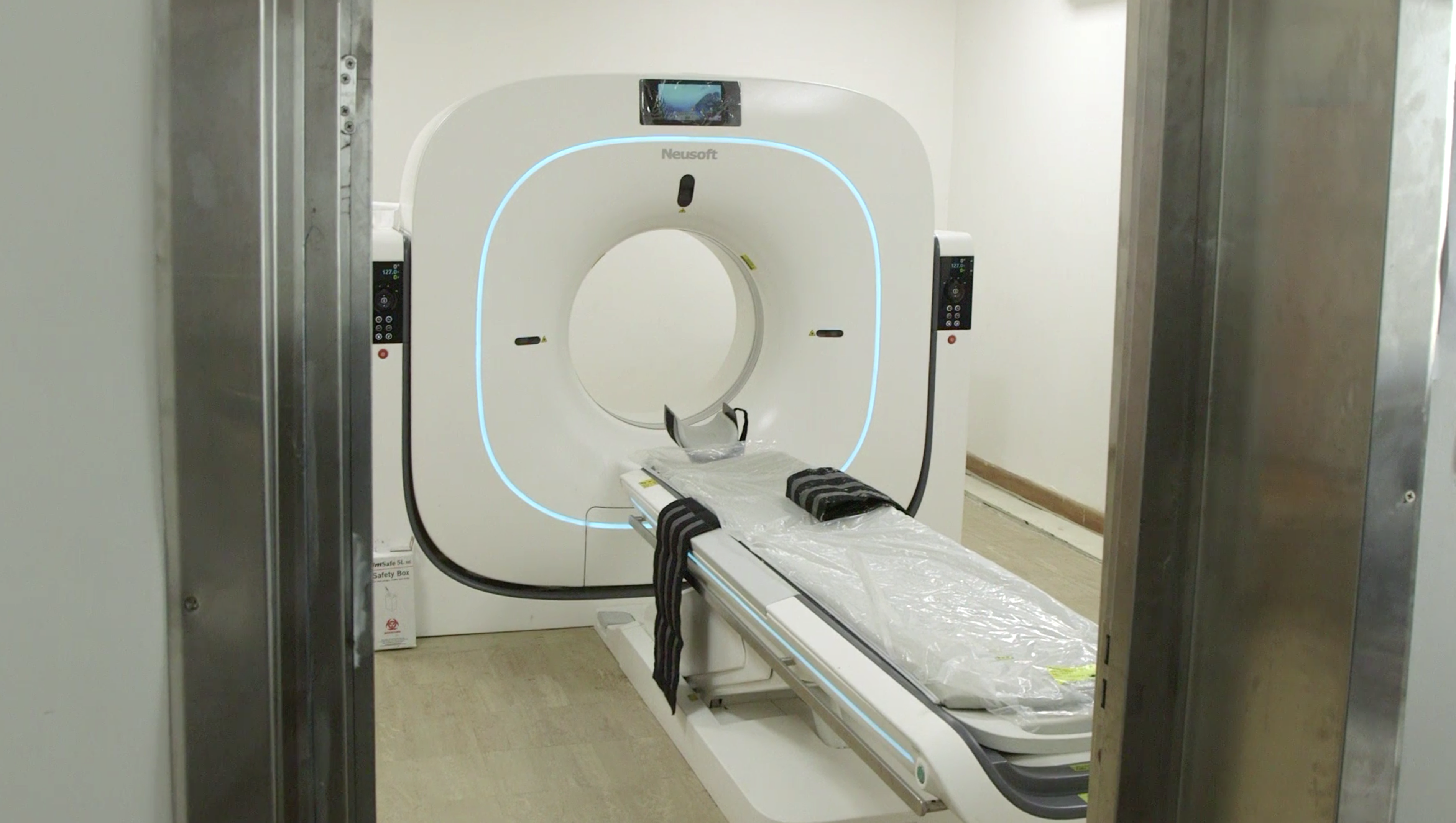

The Kenyan state has, however, spent large sums on -largely superfluous- medical machines like X ray and CT scan equipment for certain hospitals. The machines, sourced from big pharmaceutical companies in a ‘Medical Equipment Supplies’ scheme -at a cost, so far of US$ 257 million-, has become notorious in Kenya for its opacity, lack of consultation and suspicions of kickbacks for state officials. Kenya’s Senate Finance Committee found last year that at least “half of the (…) hospitals (that had been listed as recipients, but had never been consulted, ed) in the contract have not utilised the equipment,” either because they did not have the trained personnel or even the electricity to use these, or already had similar machines. Kenya’s Auditor-General Edward Ouko told reporter Joy Kirigia that “in some cases we have actually gone to (regions) when things were delivered, but there is actually nothing there or there is something but (it is) in boxes.”

There is actually nothing there or it is in boxes

Repeated attempts by Kirigia to obtain comment from the Ministry of Health were unsuccessful and the contracts with the pharmaceutical companies remain undisclosed. The payments of Kenyan taxpayers money to the pharmaceutical companies are nevertheless ongoing: at least another US$ 118 million is still to be spent on similar equipment. According to figures from the Kenyan Ministry of Health’s Human Resources Strategy plan, an estimated 165 000 patients die in Kenya annually of diseases like cancer, TB, Aids and pneumonia, many of these under similar conditions as Esther Wambui, without receiving needed treatment.

Trapped billions

In Nigeria, similarly, budgets meant to provide primary health care, as well as education and other services on local levels, were found ‘trapped’ in a gigantic bureaucracy. Close to US$ four billion in annual government allocations for local municipalities had not been paid by Nigeria’s federal state authorities to the local level in the past twelve years.

A spokesperson for Kogi State governor Attai Aidoko, approached by reporter Theophilus Abbah to comment on the dilapidated state of a clinic in that region said that the governor “had done his best to bring that project to his constituents” and blamed the “local level” for the fact that the clinic had never served any patients. When in a subsequent phone call the reporter wanted to ask about the allocations that should have been paid out to the local level by the governor’s Kogi State, the aide did not pickup the phone, nor did he reply to text messages. It remains unclear what has been happening in Nigeria’s states to the estimated US$ 42 billion non-dispensed over the past twelve years.

The team found that corruption was not always to blame for the money wastages; it was often also a question of dysfunctional systems and bad governance, which, as was also noted, create more opportunities for those who do want to steal. Ghana, for example, has repeatedly invested millions of dollars in tomato canning factories, meant to process the harvests of the country’s famed tomato farmers, who in the northern regions make up to seventy percent of the economically active population. However, bad management of the canning projects has led to bankruptcies and a halt to operations every time. A 2010 research study by the International Food Policy Research Institute IFPRI in Washington, USA, mentions “frequent breakdowns resulting from a lack of spare parts and obsolete machinery, lack of technical competence, bad financial management and poor marketing” as causes for the failures.

Frustration will force you to commit suicide

Absent or failed government assistance to the tomato farmers has led annually to suicides since at least 2007. Interviewed by reporter Zack Tawiah, municipal CEO for the Tano South region in Ghana, Collins Offiman Takyi, confirmed that two farmers -identified only as Abuu and Appau- did so last year, drinking a “pesticide called Aerocon.” “Two of them drank it and they died because they had borrowed a huge amount from money lenders,” Takyi said. Farmers Kwabena Asante and Issahaku Ayama, interviewed by Tawiah, confirmed being on the verge of desperation. Asante said the government was ‘neglecting’ the farmers whilst Ayama, a former regional ‘best tomato farmer’ award winner two years in a row, said that indeed “frustration will force you to commit suicide by poisoning.”

There is, as said above, no indication that corruption was a factor in the bad management of the tomato canning factories or the lack of assistance to the farmers generally. However, in Ghana, like in the other countries where the team investigated, responsible state officials refused to comment when asked questions about their duties and portfolios. Repeated phone calls made over a period of a week to Ghana’s Ministry of Trade were not met with a response. Phones were either switched off, or just kept ringing, or were answered with a promise that the call would be returned, which then did not happen.

Based on the finding that money often is available to provide services to citizens, and that proper management of these budgets seems crucial, the AIPC team recommends in its conclusions that a dialogue involving civil society and good-governance-pioneers in the state structures (of the six countries) as well as donor countries and development partners should take place on how to improve the situation.

* This investigation was done by an AIPC team consisting of David Dembélé (Mali), Muno Gedi (Somalia), Zack Ohemeng Tawiah (Ghana), Theophilus Abbah (Nigeria), Chief Bisong Etahoben (Cameroon), and Joy Kirigia/Africa Uncensored (Kenya). The project was coordinated and edited by Evelyn Groenink (ZAM). Read full ‘Public Disservice’ report can be seen here.