“In our department we buy twenty five boxes of mineral water every month,” says the procurement official for the Sports Ministry in Bamako, Mali.

“In the shop you pay the equivalent of two-hundred and fifty dollars for that quantity. But we pay double that, about US$ 500.” Where the other half of the five hundred dollar goes? To ‘anonymous middlemen,’ is the routinely given answer to anyone who asks questions about Mali’s opaque state expenditure processes. In this case: to distributors operating for the water empire of one of the most powerful businessmen in the country, Cyril Achcar.

Two hundred and fifty dollars may not seem much. But counted over a year it adds up to three thousand dollars, and multiplied by Mali’s thirty government departments in the capital Bamako alone, that is ninety thousand dollars, per year, overpaid from state resources in the extremely poor country, just on water bottles. Achcar sells grains and flour and flavoured drinks to the state, too.

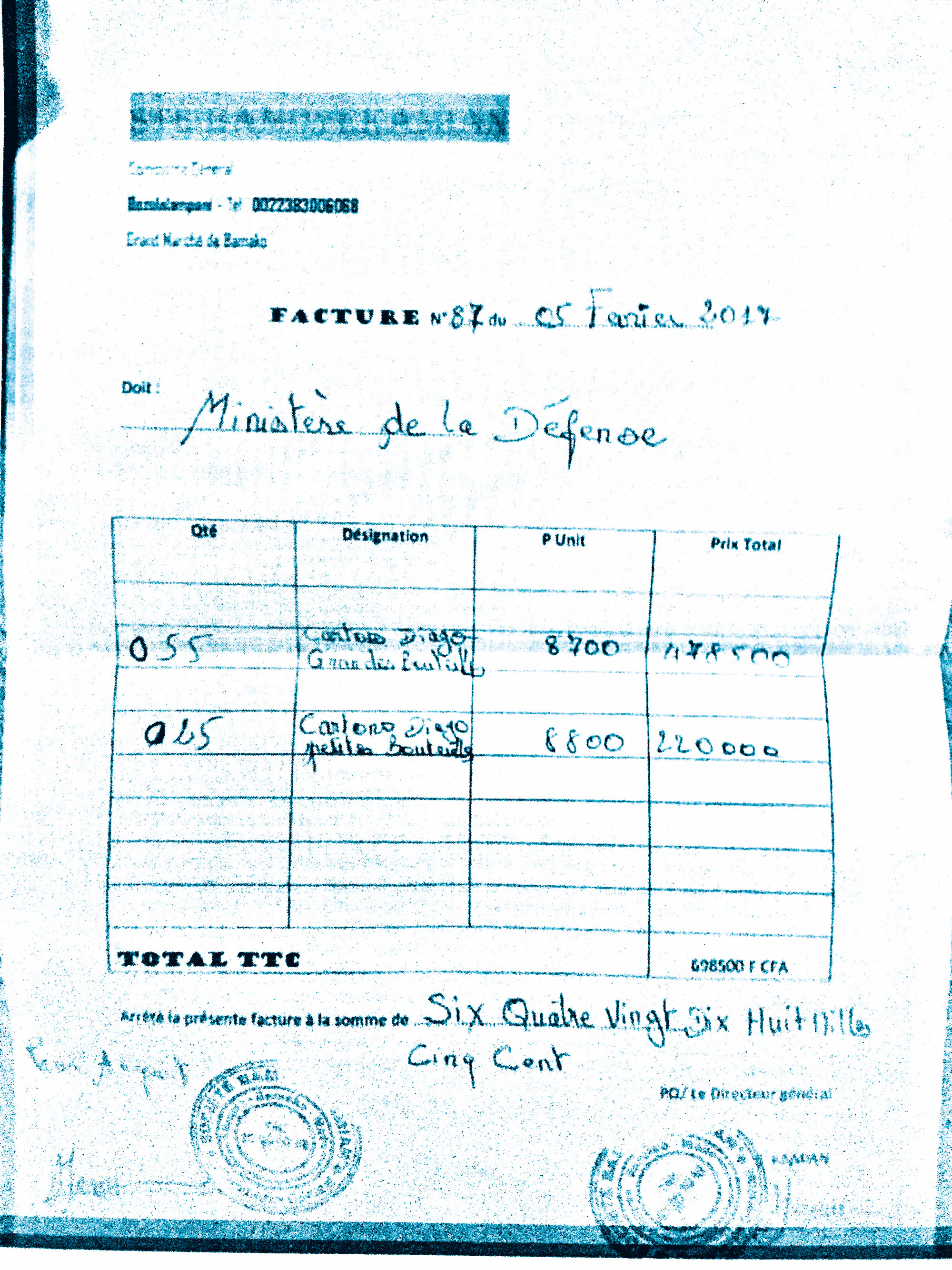

Officials from two other government departments – an administrator at the secretariat for Economy and Finance, and a member of the cabinet of the Minister of Defence – confirm that their departments also acquire the Eaux Minerales de Mali from powerful businessman and good friend of many ministers, Cyril Achcar (dubbed ‘the Kingmaker’) at double or even triple the price of ordinary consumers. One invoice in our possession shows that the Ministry of Defence on 18 October 2017 paid the equivalent of US$ 20 for a box of ten bottles, triple what it should have been.

There must always be an excess payment

Representative Moustapha Camara of competing water company Kati – encountered in the corridors of the Ministry of Justice – confirms despondently that he and his company don’t get very far trying to sell their water to the government. “If you see one of our bottles here, you can be sure that the department did not buy that.” With regard to the water that is bought, “there must always be an excess payment,” confirms the administrator in Economy and Finance. “The director and the minister take care of that together. From the state budget of course.” “Our financial department people just always ask (the people who deliver) what they must put on the invoice,” says the Defence cabinet member. “The surplus is divided between the Ministry and the distributor.”

Defence is a very big customer indeed, thanks to the many military role players and activities in Mali. Additionally, Achcar’s Diago water also supplies the international peace keeping forces, negotiations, conferences and regional alliance units based in the country.

A delusional price

Eaux Minerales de Mali (EMM) denies in the strongest terms that it overcharges the state. “We don’t sell at such a delusional price,” is spokesman Sidi Dagnoko’s answer to questions. “We also sell no water directly -only through our network of distributors. No invoice issued by EMM reflects a sale of this prohibitive amount.” According to Dagnoko, EMM sells the water to its distributors of between nine and ten US$ per box of twelve bottles. Or even less than that: an invoice, made available by FAT distributors who sell EMM waters, mention a price of US$ 7,50 for the same box. With the shops selling at ten US$ for such a box, that is a regular mark-up to be shared between the distributor and the shopkeeper.

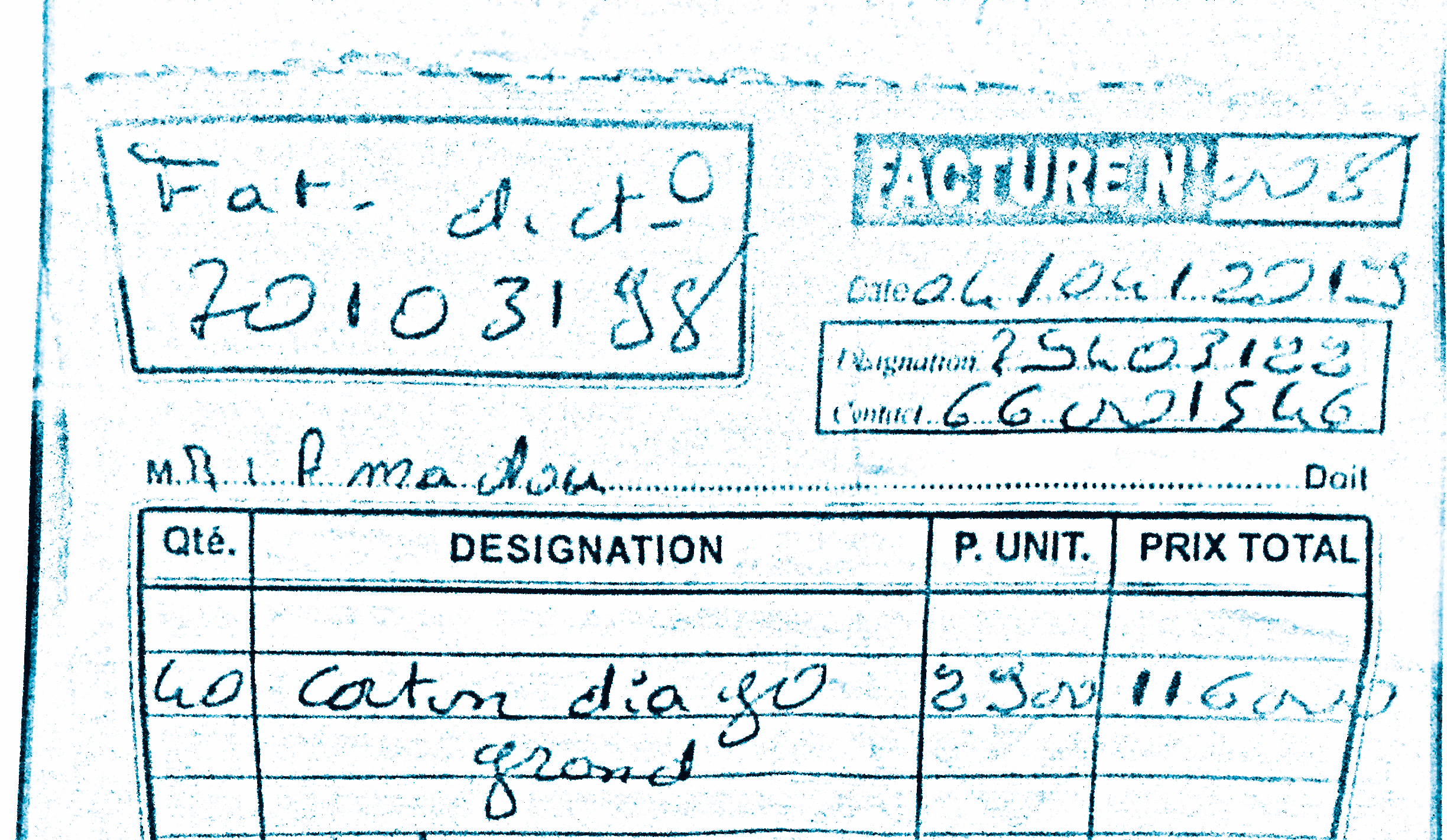

So why are the government departments paying so much more for the water of Eaux Minerales de Mali? Asked for an invoice that shows a payment from a Ministry, FAT declines, and so does fellow distributor Bamoye Kamian, named by our sources as the distributor their department pays the inflated prices to. Bamoye Kamian ‘s spokesperson, Lassana Sissoko, confirms his company buys the water from EMM at the same wholesale price as other distributors, but refuses to answer any questions relating to the amounts paid to his company by the government.

Diago water, many consumers say, isn’t even the best water around. It has happened at more than one conference that participants were disconcerted to find the water in their bottles less than transparent, sometimes even with suspicious bits in it. In early 2019, foreign technical partners meeting at the High Authority for Communication in Bamako were stunned when their bottles of water exploded as people were opening them.

Personal friends

The Achcar water monopoly is also not good for Mali’s business environment. The government, in favouring EMM’s Diago water, leaves no less than three other local companies: Oasis, Tumbuktu, and Kati, close to moribund. “Diago coins eighty percent of the entire water market,” says former Oasis executive Moussa Sidibé, adding that “for several decades, no other operator has had a chance to maintain and develop.” But why do the distributors of Oasis, Timbuktu and Kati not also simply give the departments a good share, like it appears EMM does? Kati salesman Moustapha Camara indicates that he would be quite willing to discuss such arrangements, saying that he understands that “this is the condition for markets of this kind” and that (if given a chance) “we will be no exception to the rule of overcharging and sharing.” But somehow, apparently, they can’t match what EMM can offer.

No other operator has had a chance to develop

Oasis’ Sidibé suspects that EMM remains the favourite because of two factors. Firstly, Achcar is a personal friend of many high profile Mali politicians as well as the chair of Mali’s employers’ organisation Organisation Patronale des Industriels du Mali, OPI. Secondly, Sidibé considers that, thanks to the strong government connections, EMM will be in a position to manage the middlemen. “He (Achcar) uses the distributors to outbid us. You cannot just transfer the responsibility for the overcharging to the distributors. You as the manufacturer of the product should supervise the tender process. If you don’t do that, you are not serious about your image.”

Image is indeed something EMM does not seem overly worried about. Its distributors’ invoices don’t even carry a heading. Any-body trying to follow a paper trail will be confused by the seemingly hasty scribblings of numbers, with no reference to who is paying whom.

In a way that is surprising, because EMM is, it must be emphasised again, not a two-bit shop but a very large company indeed. The researchers of the Extractive Industries Transparency Intiatiative (EITI) rank EMM as the eighth richest company in the country; the seven ranked above it are all gold mines. Owing his empire to his dad, grey-whitish haired, round-bespectacled patriarch Gerard Achcar, -who was known as the ‘kingmaker’ in Mali politics before his son-, Cyril Achcar has been introduced by papa to all the right people in all the right places, and has taken to his powerful position with great zest. In an interview in Le Monde, published in 2017, he says that “In Mali, it is better to be feared, it is a country of lawlessness. But I do not use my power to destroy.”

Money to Panama

Cyril Achcar’s power is centralised in Achcar Mali Industries (AMI), the overall conglomerate that combines his water, lemonade, grain and flour and pastry activities. AMI is the vehicle through which, the Panama Papers show, he has invested substantial parts of his Mali income in his Panama-based offshore company Grieta Consulting.

The Panama Papers have exposed an avalanche of off shore money transfers to Grieta. According to a contract with Grieta, monthly payments as large as US$ 200,000 were made by EMM to Grieta in 2016 in ‘commissions for services’ to a total of US$ 745,000. There were also other off shore transactions, such as a transfer of US$ 1,700,000) from Mali to the CFM bank in Monaco, another tax haven, in the same year.

Sidi Dagnoko, spokesman for the Achcar group, said there was nothing suspicious about the transfers. “Grieta was a company that pre-financed investments and purchases for the GMM and EMM companies, and it was remunerated in this way,” he says, unperturbed by the fact that Grieta, EMM and GMM are all owned by Cyril Achcar, who is therefore invoicing himself for work done by him for him. “These (amounts) were for (Grieta’s) financial assistance. They have been taxed in Mali as services rendered abroad.” Prodded further, he said that “if there is anything wrong it is up to the institutions of control to look at that.”

If there’s anything wrong it is up to the institutions to look at that

“Mr. Achcar is an economic operator guided by the lure of gain. For many decades, he has taken advantage of the weaknesses of previous regimes to enrich himself. He is very skilled at avoiding tax, “ says a fellow businessman in the OPI. A 2016 report from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative EITI lends credence to such suspicions. (At least with regard to the water company EMM, because its focus on extractive industries means that EITI is only concerned with the mineral water, not with the grain and flour.)

The EITI report criticizes EMM for using only its water income tax number, whereas it also sells flavoured drinks, which should be declared under another; it also records a lack of information on Achcar’s empire’s assets. But most glaring in the report is the difference between the income that EMM had from water in 2016 according to EITI’s account, and the income that EMM declared to Mali’s tax authority. While EITI’s own count results in earnings of US$ 2,645,000 in that year for EMM on water alone, the public treasury reported – also to EITI – that EMM had declared only slightly more than half that amount, US$ 1,415,000 ,in revenue. The EITI report further states that EMM did not provide detail on its receipts of payments. It also does not list any information at all on its payment of social contributions, a duty of each tax payer in Mali.

Very busy

It is not known if Mali’s tax authority has ever acted to obtain more revenue from Achcar. But an Auditor General’s report over 2007 does not inspire much confidence that at least in that year it was interested in doing so. According to the report, Mali’s tax agency the Directorat General des Impots (DGI), then irregularly relieved Achcar’s grain and flour company Grands Moulins du Mali of VAT duties. “The documents provided by the DGI do not prove (proper monitoring of) the statements of letter No. 5136 that suspends VAT for the benefit of GMM,” the auditor- general then noted. It could not be ascertained whether GMM is still not paying VAT on its products.

Phoned for comment on this and other tax matters, EMM’s spokesperson responds that he needs to check and that the company is very busy. A later emailed query remains unanswered.

Malian tax expert, Alassane Cissé, denounces the tax evasion in the poor country by some “barons of the OPI,” as he calls them. “We don’t collect enough tax. There is impunity and favoritism. If we can only achieve better computerisation so that we can control and trace all payments, then we can weed out the unscrupulous officials who deal with large payers for to help them erase their debts.” An official at the Mali state procurement office would like to see a concerted effort for more transparency in the state’s buying procedures. “We should uncover the whole chain of persons involved in such contracts, from the Minister to (our own) officers and to the Director of Finance and Equipment.”

Why would you pay tax in Mali? What for?

That the official prefers to remain anonymous for the time being, is not surprising. According to a former Mali diplomat -whom we, by coincidence, run into in South Africa- the overwhelming majority of those who are in command of state structures in the country just don’t want to take such measures. “They don’t work, all they do is chase contracts and projects for a share,” he says, explaining that in a way this is understandable because “the salaries are low; even a minister or director general earns no more than US$ 500 per month.” He also understands that few people feel like paying tax in Mali. “What would you pay for? We don’t have good education, health care, or even proper water distribution. People really don’t feel like paying tax as long as they see no return for their money.”

Asked how, in that case, anything will ever change, he pauses. Then says that officials should actually be ethical and work to deliver services to the people. “If they would work according to their conscience, then indeed maybe more people would pay tax and Mali could move forward. But for now the state remains just very corrupt.”

Asked to comment on the overpayment for Achcar’s water bottles, the various ministries’ spokespersons say they don’t know about the issue or refuse to answer. “Maybe there was a contract before I started here in 2016. I don’t know,” says Mahmat Traoré at the Finance Ministry. “I will ask the minister.” He does not come back to us after that; neither does Minister Boubou Cissé. The spokesman for the Ministry of Sports does not answer the phone. Justice Ministry’s spokesperson Daouda Kamate says that he cannot comment on the subject and that we should “send a letter via the post to the ministry’s general secretariat.” Lastly, the communications adviser for the Ministry of Defence, rebukes us: “We have a noble mission to fulfill in defending the security of Mali and we don’t have time for senseless questions.”

*Also France

Except for Panama and Monaco, the Achcar family is also well connected in France. In 2005, the French news site Médiapart revealed that Gerard Achcar, Cyril’s father, benefited from a two-thirds write-off of his estimated tax debt of four million Euro in that country. (Médiapart’s report that former minister Jean Francois Copé assisted Achcar with the write-off were vehemently denied by those involved, with Achcar saying he did not even know Copé). Wealthy businessman Nicolas Bazire, CEO of the luxury brand Groupe Arnault (Louis Vuitton, Moët Hennessy) is related to the Achcars by marriage: his daughter married another son of papa Gerard Achcar. The Achcars’ AMI Group has – next to a considerable loan from the World Bank’s sister organization, the International Finance Corporation – also benefited from ‘technical assistance’ from the Agence Française de Développement.

The research for this article was assisted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, of which David Dembélé is a member.

This story is part of a new report, The Associates. Handling Business for the Kleptocrats, published by ZAM and the African Investigative Publishing Collective (AIPC).

Participating journalists: David Dembélé (Mali), Purity Mukami (Kenya) with help from Margot Gibbs at Finance Uncovered, Theophilus Abbah (Nigeria), Estacio Valoi (Mozambique), Charles Mafa and John Mukela (Zambia), T. Kaiwonda Gaye (Liberia).

#TheAssociates #aipcofficial @zammagazine Investigative. Expose. Mobilise. The AIPC ZAM Story Fund needs your support. Send your donation to: Account number NL 65 INGB 0007 4538 82 Swift Code INGBNL2A