Reading Marechera.

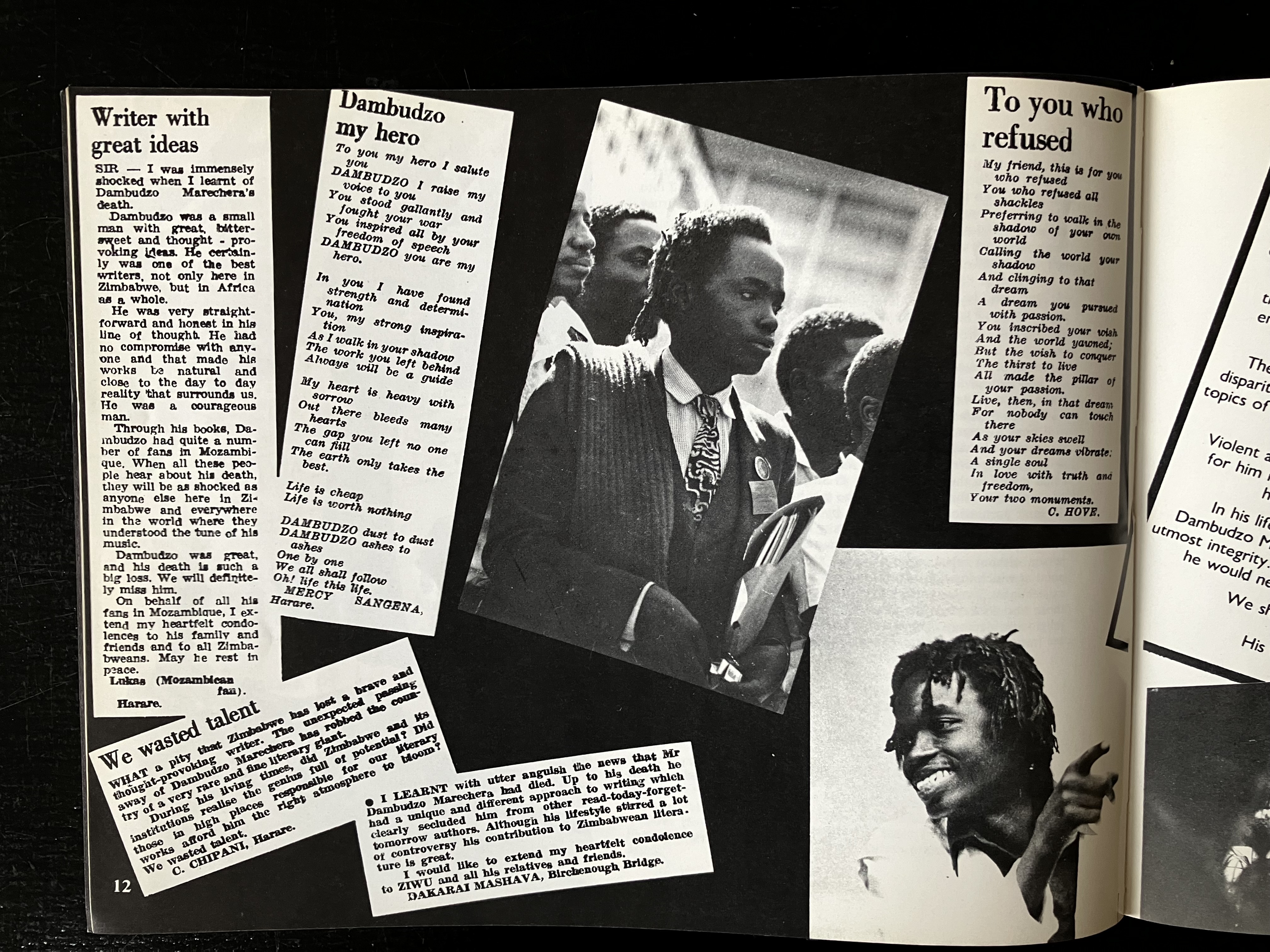

Marechera was made into a mythical figure, Shaun Matsheza writes, but behind the myth is a real man who tried to express the mess in which he lived in the most honest way possible.

Until recently, it has not been easy to get one’s hands on a copy of Marechera’s books, at least in Zimbabwe. Copies of House of Hunger are as elusive as Marechera himself must have been, back in the day. So for many people in his home country, reading Marechera has not been easy, even at a simple access level. This will hopefully change soon with new editions being published.

There are many ways to read Marechera, and an infinite number of routes through the mindscape he forcefully weaves with words. Diving into a Marechera book is, quite literally, to experience a mindblast. I read Marechera first as part of the literature class at the University of Zimbabwe. I had long heard of him by then, of course, but had never gotten my hands on any of his writing. House of Hunger gave me the first foray into his blazing intellect, and it is not trite to say that I was never the same after that. Marechera was proof that it is possible to know the rules, break them as comprehensively as you can, and yet remain respected, acknowledged, and indeed, become a legend?

In his interview with Alle Lansu, Marechera describes how he thinks of his work as “literary shock treatment”, that is, he seeks to present people with an image so shocking that it makes them double-take and see reality anew. He saw himself as a 'Cassandra figure', cursed to see the future, but to not be believed. And indeed, his prefiguring of the post-colonial state of Zimbabwe was rather uncanny.

What stands out about his writing is its sense of urgency: things are happening, in motion, and there’s nothing one can do to stop them, like thoughts on a carousel through the brain. When people make him a 'mythical' legend, they make him that, a mythical being who spoke fantastical gibberish. Yet he spoke the truth as he saw it, and those who hated its stench passed their judgement on this doppelganger who dared present it to them. This is why Marechera is simultaneously enticing and repulsive, interesting and detestable.

But he was a real man who tried to express the mess in which he lived in the most honest way possible, and that necessitated his obscenity and scatology. His writing does not lead to clarity, a reality seen through clear panes of glass. Rather it leads to Rorschach images that demand further explanations, but images that would not have been seen had he not signposted them.

Many aspiring writers in Zimbabwe have mistaken Marechera’s eccentrics as the key to his literary success. It is much like a musician trying to be like Michael Jackson, and then imagining that all it takes is to always wear a white glove and some silver studded outfits. Yet Marechera was a master of his craft, and when one reads House of Hunger closely, one gets to realise just how much he draws from the canon of literature in English.

It is impossible to distil all the elements that created him, but there is no denying that Marechera read voraciously, and that his biography played a great role in determining the themes in his writing. He ‘writes poverty’ without subtlety. His is a brutal intoxicating (intoxicated) take on the colonial, and post-colonial condition. But while the poverty and violence of the colonial seeps through his work, it is also an extreme version of what many Zimbabweans know. The extremes are very extreme, and the lows abysmall.

To claim to understand Marechera is to take hold of the wrong end of a double edged sword. There is understanding, intelligibility, and then there is understanding, getting. I never got Marechera, but I understand him. He wished for better for his people, and maybe that process begins with getting them to see just how bad is the condition from which they have to elevate. His works remains relevant to this day.

When he claimed he was a writer for all time, he was right.

Shaun Matsheza is a writer and content creator. He is a communication specialist from Zimbabwe, with extensive experience as a content strategist, editor, producer and trainer in multimedia journalism and creative storytelling. Hew worked for RNW (Radio Nederland Wereldomroep) en is currently at the staf of TNI (Transnational Institute) in Amsterdam. Shaun's passion lies in the link between storytelling and people's perceived ability to effect change in their societies. A lifelong learner and ardent believer in freedom of expression, he strongly subscribes to the creed that: 'When people tell their own stories, they become protagonists, people who make things happen.'