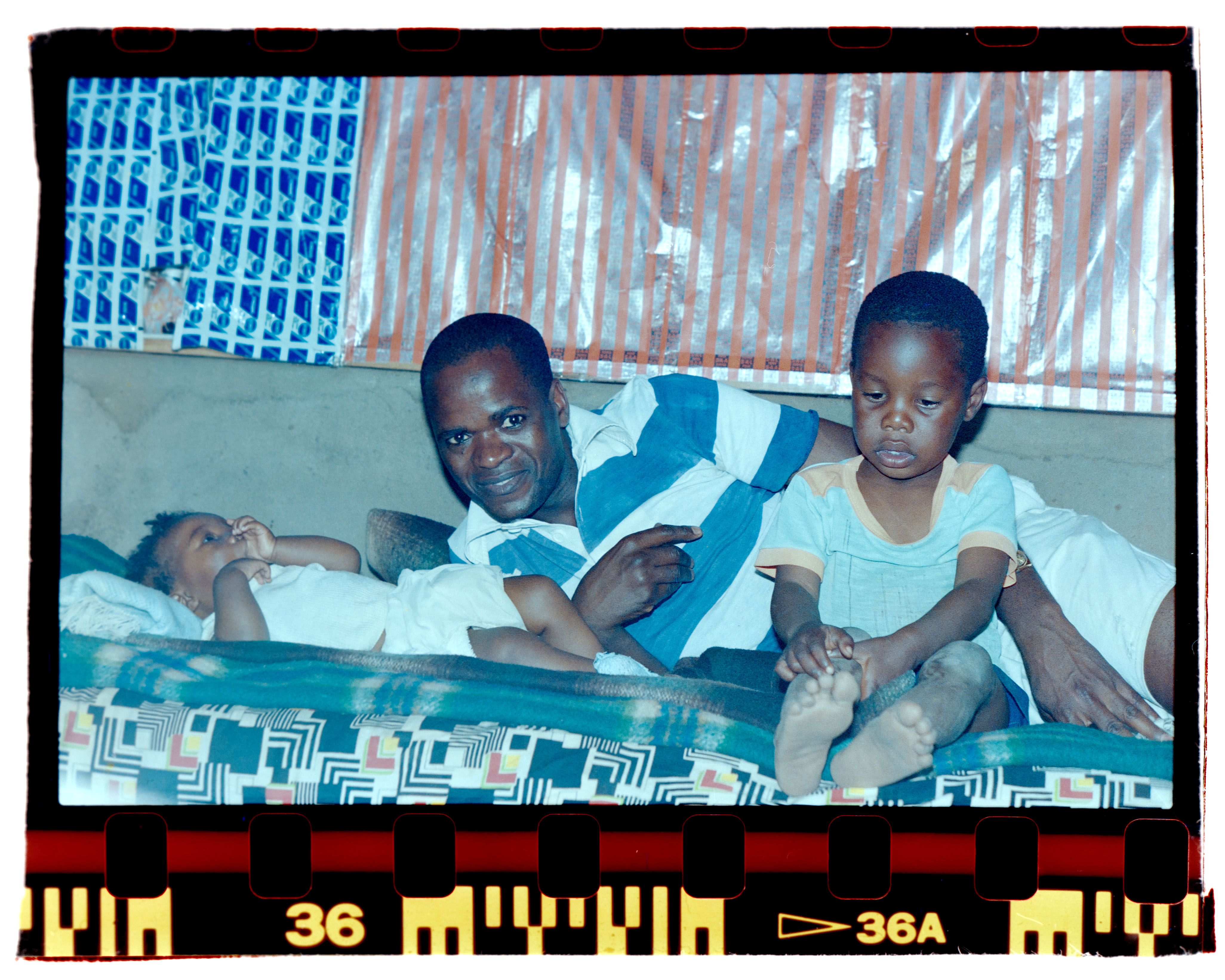

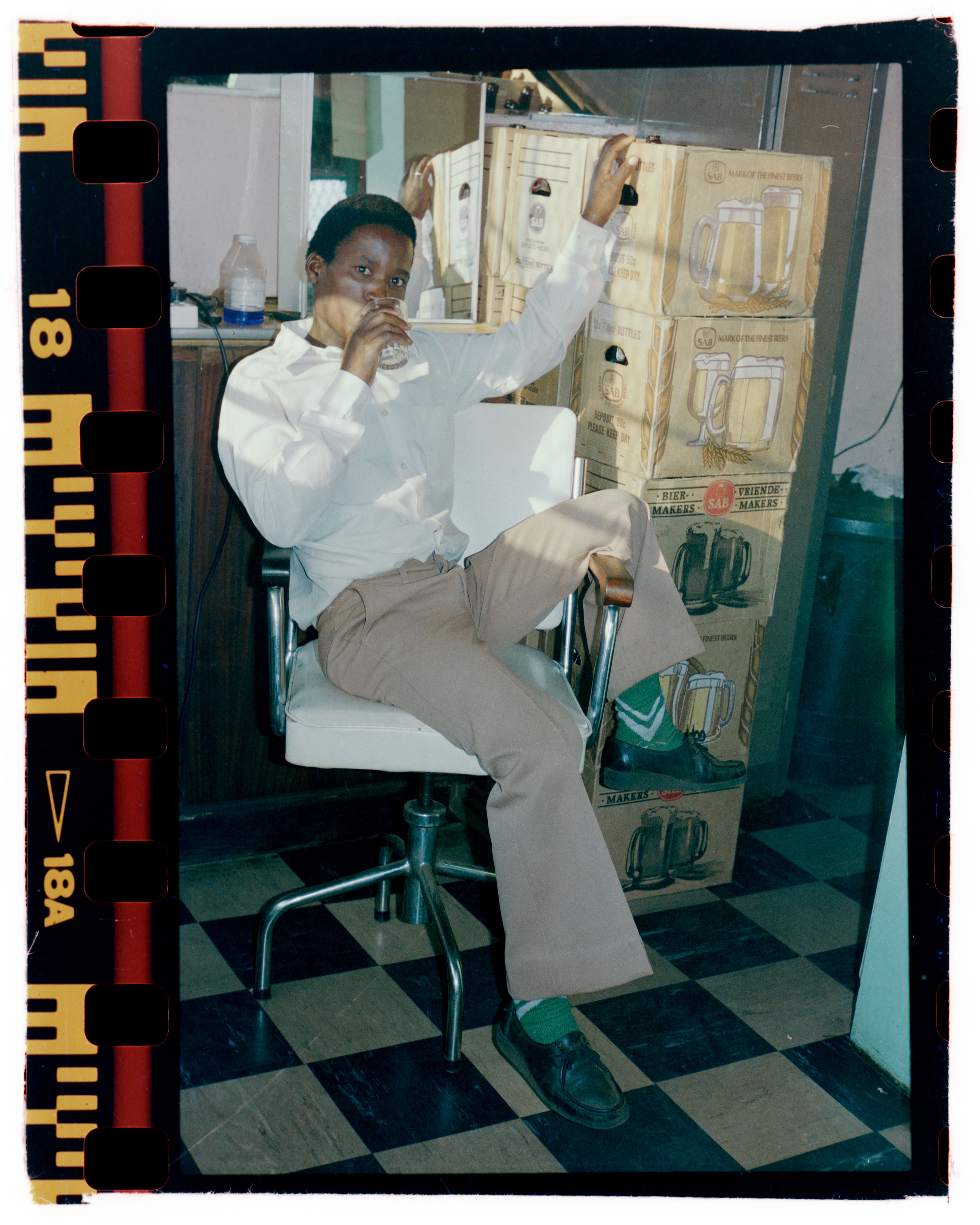

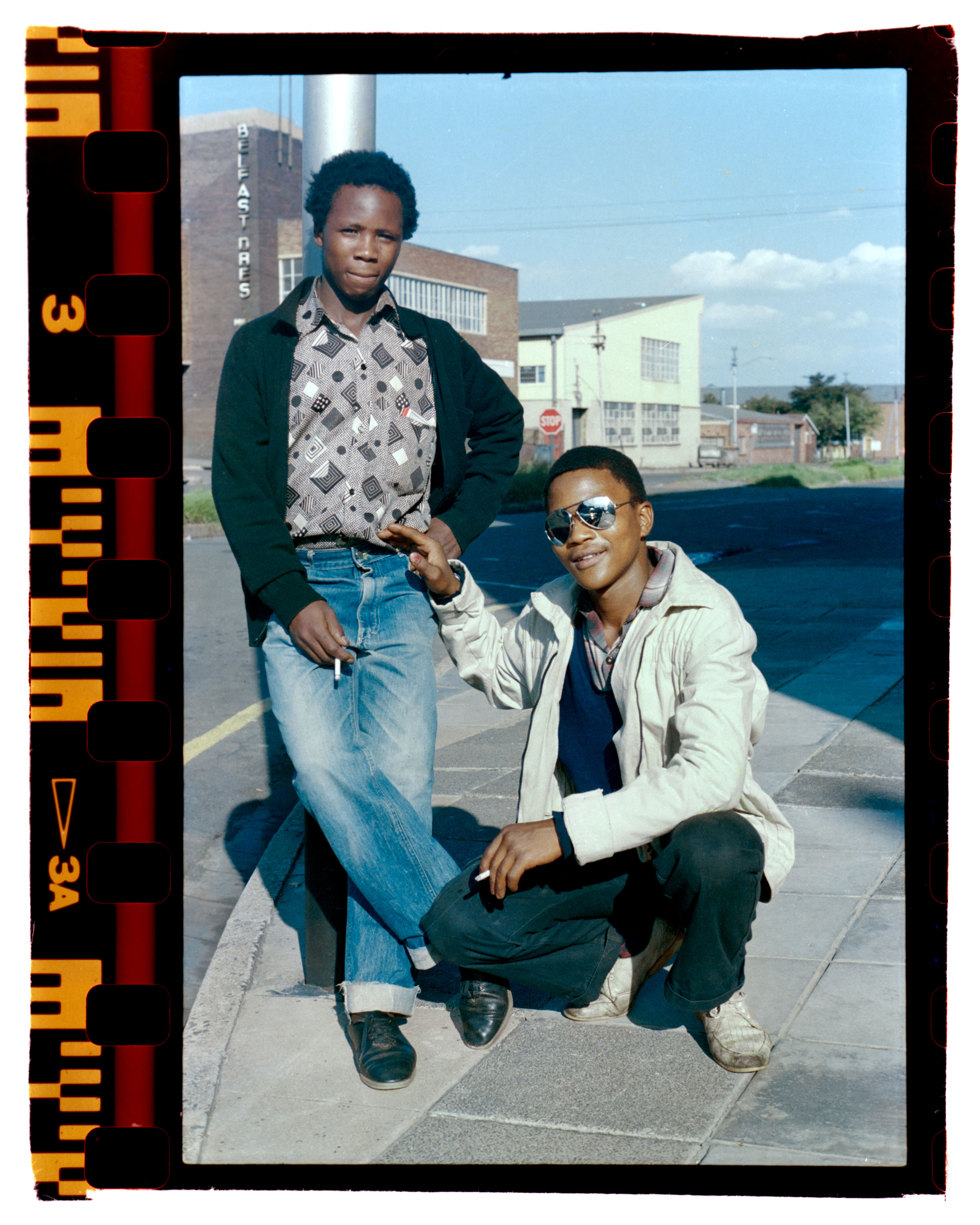

During the last decade of Apartheid in South Africa, William Matlala (1957) made photographs of and for the people around him. William and I met because of his contributions to a research project about cultural responses to the consequences of mining in the Witwatersrand. He took me on a tour through his life, captured on a hard drive, containing scans of negatives. I instantly fell in love with the photographs, in which the people posing present themselves as they wished to see themselves and be seen by their loved ones. In fragmented conversations, taking place over the course of a week of working together, William began to help me understand the early days of his photographic practice, the conditions in which it unfolded, and how it led to a professional career devoted to documenting labourers and their continued struggle for better working conditions. There is much more to learn from William and the photographs he made. But here’s a beginning.

“I got my first camera in the early 1980s when visiting my mother while she was cleaning the house. She was about to trash it, but allowed me to take it. I started using it to make some extra money.”

Workers migrated from rural areas and would then be living in urban hostels. I was one of them. Fellow residents of Kwesine hostel, people living in Katlehong township, east of Johannesburg, and my co-workers at Trimpak – a packaging factory – were my main clients. They would ask me to photograph them individually, in small groups, or during events. I was paid per picture taken. Some just wanted one exposure, others several. Small groups were good business, because several prints were needed of one shot. They gave me a deposit when I took the picture and then – upon delivery of the print – the balance.

Most of the people I photographed were in an environment that was familiar to them. They usually knew where and how they wanted to be pictured. When people were visitors to the location in which they were photographed, they often needed some help to find the right pose. I then gave directions, telling them, for instance, that they could pretend to walk.

People dressed for the occasion. They liked to be photographed with signs of prosperity such as a radio. They wanted to show that such a thing was around where they lived.

Photographs were either kept in albums or given to family members. All the men in the hostel had family in the homelands [ethnically defined apartheid areas]. Many families lived partially in the village and partially in town. Just like my wife and I did for most of our married lives, they would commute when they could afford it. Photographs are, in my language (Northern Sotho) and culture, thought of as a copy. My pictures were copies, senepe, of the people I photographed. They showed the family in the village what life in the city was like, and what resources were accumulated thus far. The photographs would be given to family members in the village or placed in personal albums kept in the township home.

My co-workers were paid weekly, so I knew customers would come after work on Friday, or in the mornings before work on Saturday, or Sunday. They figured out where they wanted to be photographed and then looked for Matlala. The women were the best customers. They requested to be photographed again and again. To my surprise, the bosses of the factory did not object to this side-business of mine. They would sometimes even ask me to come and take a photograph of them posing. I was also invited to document parties and weddings, and photographed at company end of year parties. When the workers got drunk, the event turned into good business for me.

Usually, there was about a week between the moment of taking a photograph and delivering its hard copy. When photographing my co-workers, I finished a film over the weekend. The developing and printing took three days. All pictures were printed. I would pick the prints up the next Friday and then start delivering on Saturday. If the picture was not there or not good because I or the lab made a mistake, I either did the shoot again, or – when the dress for instance was no longer available – paid back the deposit.

My clients were not interested in the negatives. Had they asked, I would not have been able to resist the request and had lost the negatives. But the way things were helped everyone. When my clients lost the picture, they came and said, ‘Remember that picture, where I was wearing this dress?’ Then I went back to the negatives, made another print, and earned a bit more money.

I volunteered with FAWU (Food and Allied Workers Union). My suspicion is that the pressure to start working with the union led to the bosses filing for the company’s bankruptcy. When working with a union, they would have to follow the rules, do proper accounting, and they would no longer be able to employ illegal workers.

Then, in 1988, photography became my main source of income.

Apartheid was still in place, but less policed than before. From 1981 onward, marches were allowed. They intensified throughout the '80s, which eventually led to the change of government. In the late 1980s, my practice made a shift from earning money with personal pictures to the documentation of political developments, especially in relation to the labour movement and the individuals who formed its community. Black and white entered my practice in 1989, after I followed several courses in photography. Before that, there were no means for me to process black and white material. Once employed in such a way that films were readily affordable, I would shoot both black and white as well as colour. Now the restriction was based on the cost of printing. The publishers had no money to reproduce colour pictures, so they needed black and white.

These photographs were published in both company and union magazines. If I look at these photographs, I'm happy that I was there, even though the people I photographed in the 1990s campaigned for improvements they still have to fight for under the new regime.

I had to move out of the township in 1993 because of the violence that started to erupt from 1989 onward. At night, people had to guard their houses. As a photographer, I wanted to go out to photograph the results of the violence. Then people got suspicious of me, thought I worked for the ANC reporting people. There still is blatant segregation, for instance if you look at where people live. There are squatter camps, bond houses and RDP (social) housing sometimes being hijacked.

Photography lifted my family out of poverty

Sometimes people tell me that I have a certain style of photographing. I'm not sure I do. During these early years, cameras were rare in our communities; at work, in the township, and in the village. I made photographs of what people wanted to have recorded. It has nothing to do with my choice. For me to get money, I needed to do what people asked me to do. And I did make good money. Photography lifted my family out of poverty.

Working for the Union lasted only something like 2.5 years. In June 1992, I was retrenched because, they said the department of photography was too expensive to continue to run it. But I never broke up that relationship.

Then, in 1993, the South African Labour magazine, the magazine of all the workers in the country, called me to work in their propagation. Now I was also present to document negotiations with the employers, and became aware that I could go deeper and deeper into the labour movement. I worked there until sometime in 1994 when – again – the department of photography was retrenched. But I was called in and management told me they wanted to continue working with me as a freelancer. They said, "You do your own things, but when we have an event we want you to come in, we promise that we will call you." I worked with them until 2015. Then the organisation fell apart due to managerial problems. The people I started with had moved on to other departments. Now came new management, it got complicated, and then fell apart.

From there I kept working on my own. Slowly and slowly, working in the townships got scarce because I got busy with the requests from the unions. Eventually it fully stopped. What I did then is not easy nowadays. People have their phones and don't want others to be making money of them. So I go for particular things, such as events I hear about. Even while working with all those organisations, as someone who comes from the village, I never stopped being interested in community activities. Every time I go there, I try to find out what's going on, what people are doing... and take photographs of that. When I go to the village and hear of something happening, see people dancing, I will go for that.

Even while working with all those organisations, as someone who comes from the village, I never stopped being interested in community activities. Every time I go there I try to find out what's going on, what people are doing... and take photographs of that. When I go to the village and hear of something happening, see people dancing, I will go for that.

Towards the end of Apartheid, it was easy to go to institutions and take photographs. It has become harder since. I suspect this to be the case because they don't want to be exposed in conducting mismanagement leading to a lack of brooms or other equipment.

My labour movement work is now part of the Historical Papers Collection at Wits University. The negatives are still with me, and I have scanned most of them. The hard drive has my life in there. Because of the work I did and the archive it resulted in, professors at the Society and Community Works department of the university thought that I could help them by sharing my experience. If anyone wants to know about the workers, the unions, they invite me in as an associate. They gave me an office, have me teach workshops and talk to students about the archive and the projects I am doing. With the students, I always come out of our meetings feeling like they don't milk me enough. With what I saw and experienced, there is always more to find out on why things look the way they do.”

William agreed to make selected photographs from his collection available to potentially interested people on Instagram. I showed the pictures to a fellow researcher who works with photo archives related to the independence struggle in Zimbabwe. She had just shown me pictures of armed men, heads of state, victims of armed violence. These pictures are on display in institutional contexts in Zimbabwe and meet the grand narrative of the current government in the country. When I asked her what the photographs from the William Matlala archive were about, she said: “These are fashion photographs, showing how people dressed at the time.” Many of the pictures indeed have a charming vintage fashion shoot feel to them. But I would argue that there is more to them. The struggle is there, but the people posing are not reduced to it. The fellow researcher demonstrated how we, in the here and now, generate the meaning of a photography. When I mentioned this, our conversation continued, and unlocked the potential of looking beyond photographs that relate to struggle in all too obvious ways, thereby all too often taking away the agency of the people involved. The portraits in the William Matlala archive do the opposite. Even when the struggle – as William mentioned – continues, they not only show us the past, but also hint towards the potential of truly liberated people. And then I’m not yet speaking of that other potential, of unlocking the memories and experiences of those who posed for the lens of William’s simple, but ever so effectively used, point and shoot camera.

Andrea Stultiens (NL, 1974) is a researcher, artist and educator. She conducts long term research projects concerned with images and imaginations of ‘Africa’, using her artistic practice as a research method. This results in the online sharing of findings as well as books and exhibitions. She teaches at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague and spends as much time as possible in her (other) home in Uganda. Want to find out more about Andrea Stultien's research for Groningen University’s Afrexact project on environmental histories of resource extraction in Africa? Check out this link.