In recent decades North Korean-made monuments have been unveiled in many African countries, honouring independence leaders and celebrating an African Renaissance. The South Korean photographer and filmmaker Che Onejoon has been documenting the monuments and the histories around them, their cultural significance and the relationships that they symbolize between two continents. The outcomes of his long-term exploration were recently published in a book titled International Friendship. The Gifts from Africa. Onejoon spoke to ZAM about his book and the project.

How did you find yourself documenting North Korean sculptures in Africa?

Initially I wasn't interested in North Korean culture and art that much, because North Korea is kind of like a mysterious country, even to South Koreans. But I was very interested in how the peninsula is divided into two countries, and also how South Korean militarism built my home country. My previous project is about abandoned US military camps in South Korea. Just before moving to Paris in 2012, I came across a story in a newspaper, about a North Korean monument called African Renaissance in Senegal. I was surprised to learn that North Korea had built many monuments in African countries- there was no way to reach that information in South Korea because the government still bans North Korean information and websites. Then I moved to Paris and I remembered the story that I saw in the Korean newspaper, and so I started to research on monuments and buildings built by North Koreans in African countries. I was suddenly able to easily access North Korean websites as well as South Korean information and find a lot of information that was not available to me before. Then I applied for the Musée du Quai Branly’s Jacques Chirac Photography Residency programme which I received and that’s how International Friendship project started.

How did you select the countries that you decided to work in?

When I started this project, I didn't know much about the history because it's hidden. I met a Namibian journalist, John Grobler, who was investigating the relationship between North Korea and Africa, and I learned a lot from him. North Korea was involved in military training in a few African countries; for example they provided arms to Mali and Somalia and military instructors to Zimbabwe, and even the Congolese president’s own bodyguards were trained by North Korean military instructors. I found it very interesting- I had never thought about this kind of military relationship between two countries before. During my research I also identified the main sculpture studio in North Korea, called Mansudae Art Studio, which built monuments, statues and also architecture in eighteen African countries. The studio, its artists and its production became a central interest of mine. From the eighteen countries I decided to focus on Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, Senegal and DR Congo in the initial stages of the project. I wanted to choose countries where North Korea had built significant structures, and where they had political relationships with the governments. This includes Zimbabwe during Robert Mugabe’s presidency, when he was very close to North Korea. Later, as the project developed, I visited Ethiopia, Madagascar, Sudan and Angola. So in total 9 countries.

When I started this project, I didn't know much about the history because it's hidden

The project consists of archival imagery and documents, videos, stills and even 3D-printed copies of the sculptures. Can you elaborate more about your process and how this work relates to your earlier projects?

I started my career as a photographer, but I always wanted to make films. My main medium is photography and film, but archives are also very important for me. So when I exhibit those three things together, I'm always trying to find a balance between them. The photographs, combined with the films and also the archival material, help me to convey some idea of the reality of the subject. My initial idea was to create a three-channel video installation and to exhibit on three screens, where the left screen is a North Korean viewpoint and the right screen is South Korean, both displaying archival materials and interviews. And then in the middle would be the main screen for the narrative. So, whenever I travelled I would bring two camera operators with me, who always filmed together but with different perspective. I photographed using a large format camera and I tried to put a lot of detail into every image.

Would you then say that the book is a way to finalise all of these different threads and pull them all together? I realised when I was reading the book that perhaps the best way to view the work would be in an exhibition, because then you can have all these different mediums together. How do you see the book in relation to that?

The process of making a book is totally different from making artwork for museum or gallery exhibitions. I have had some experience with making new work for white cube exhibition spaces, and for my first book, I didn't embrace the difference of the medium- I just trusted the publishing house and they took care of everything for me. For this book however, I started working from scratch together with Dokho Shin, the book’s designer. It took about two years! I am grateful to my designer for being so patient! Initially I didn't want to put my large format photographs as the book’s opening- those images are important, but the film is the main medium through which most audiences experience the work. Unfortunately, films or moving images are hard to translate into books- they have to be reduced to still images, and then they are weakened whereas the original photographs are more powerful and beautiful in the book context. So we decided to put the photographs in the beginning of the book and reduce the film’s presence. I'm quite satisfied with the result, but book’s publication doesn't mean that I finished the project because the pandemic interrupted a planned trip to Angola. I still want to extend the project a bit more, and I want to meet the North Korean artists from Mansudae Art Studio who made those monuments and buildings.

It’s about the relationships

What is the core topic of this project for you? Is it the sculptures, the politics or the relationships?

It’s about the relationships. When I started, I wanted to see North Korean art and culture through African countries. A relationship is like an abstraction- it’s hard to understand to the outsider and difficult to translate visually. But by looking at North Korean art I could see the relationship, and also the connection to the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. The main reason that North Korea supported African countries was that the US had military camps in South Korea, while there was no Soviet Army in North Korea. Kim Il-Sung wanted African support at the UN to force the Americans out of the Korean Peninsula, so he decided to offer support to African countries. In response African countries sent gifts as an expression of worldwide support for Kim Il Sung. When I started this project, its title was not ‘International Friendship’. But as I worked on it I started to understand that my interest wasn't only about sculptures but more about the visual representations of those relationships between the two continents, between Africa and the Korean peninsula. So I changed the name to ‘International Friendship’.

How do people in African countries which you visited react to these sculptures created by the North Koreans?

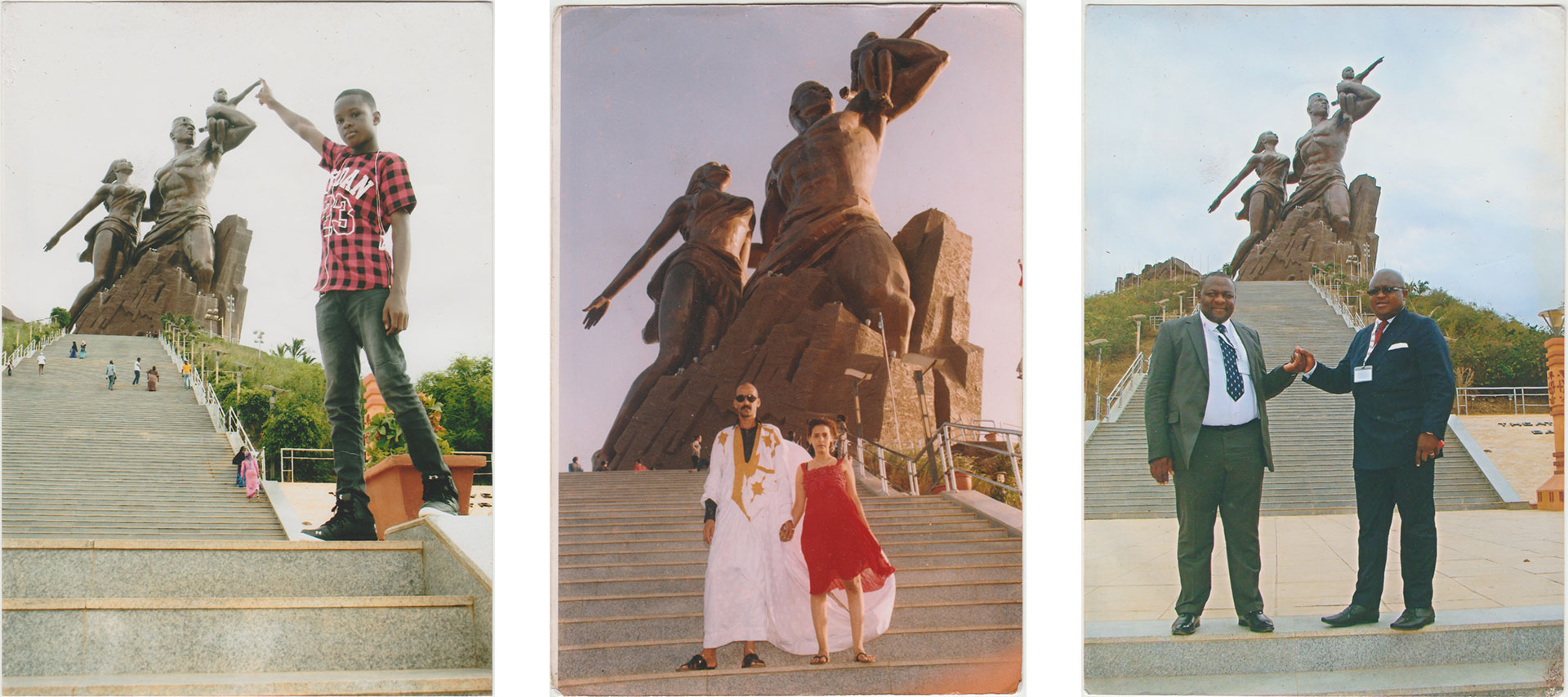

One of the one of the main reasons that I chose to visit Zimbabwe was because of a massacre committed by Robert Mugabe’s army in the early 80s, not long after the country’s independence. North Korean military instructors had come to Zimbabwe and trained the 5th Brigade which is the country’s special forces, and it was these same forces who then went on to massacre thousands of citizens (more than 20,000 people were killed in a series of atrocities known as the Gukurahundi around the area of Bulawayo. When North Korea built a statue of the Vice President, who was from the same tribe as those who were massacred, the Ndebele population group, it was highly criticised and people wanted to destroy it, and in the end the government had to remove it. So that’s the background story of the cover image of the book. The back cover shows the empty pedestal. Zimbabwe's case is representative, too- other countries have also had trouble with North Korean art. Senegal is different. Former President Abdoulaye Wade didn’t invest much in development but then he spent what seemed like an impossibly big amount to build the African Renaissance monument. It was constructed by Mansudae Overseas Projects for US$ 27 million. People criticised it- they didn't like African Renaissance in 2010 when it was built, or in 2013 when I was there first time. However when I went there again in 2016, by then it had become a very popular site- young people were dancing, and training and exercising, it is like in a public park. That's why I included the souvenir photos in the book. I bought them from souvenir photographers who work near the monument. In 2013 there was no one, but in 2016, there were a few souvenir photographers, which means there were many tourists. I saw this as a sign that people’s minds have changed.

Why do you think African Renaissance is so popular with people these days? Did you ask anybody about it when you went there a second time?

There is a park belonging to the monument which is like a hill. And it's perfect to skate, a perfect place for skateboarders. So young skateboarders really love that area. And I don't know how many stairs you have climb to get to the top, but the huge staircase is perfect for exercising so many people exercise there. It’s like the Statue of Liberty in New York, you know? The monument is still controversial though, because most of the Senegalese population is Muslim, and the female figure has an exposed chest. Many imams have publicly criticised the monument as being against their culture and traditions.

Why do you think African governments ask North Koreans to supply these monuments instead of asking their own artists?

There are two reasons that most African countries still prefer to work with North Korea. Firstly, they are cheap, and they have a very high level of skill. There is not much difference between North Korean statues and Western statues in terms of technique- they use almost the same techniques. The second reason I think that African countries chose North Korea is their bronze casting skill. Only the North Koreans can do that. North Korea has a big bronze casting culture partly because they are constantly making memorials to the Kim dynasty and to communism. I think initially when they were donating or giving gifts, sculptures of dictators and whatever, it was more to have Africa on their side in a way. So it was more of a sort of diplomatic thing that they were doing and now it is more purely economic- for the North Koreans it has become less about diplomacy and is now a business model.

Che Onejoon is a visual artist and filmmaker. One of his first projects involved photographing Seoul’s red-light district, which began to decline after the anti-prostitution law took effect in 2004. He also made short films and archives that capture the trauma of modern Korean history by documenting the ruins of the global Cold War: in the form of bunkers constructed in Seoul during the immediate aftermath of the Korean War, and the U.S. Army camps in South Korea vacated when the soldiers redeployed to the Iraq War. In recent years, Che worked on a documentary project about the monuments and statues made by North Korea for many sub-Saharan African nations. His on-going project seeks to create a photographic work, film and installation about Afro-Asian culture and identity.

You can find more information about International Friendship. The Gifts book from Africa book here.